Learning from Experience

by Searching for Insight

This page has not been revised

since May 2001, but

the version on another website has been revised and is

combined with other ideas about education and motivation,

so I strongly recommend that you read

THE

REVISED VERSION.

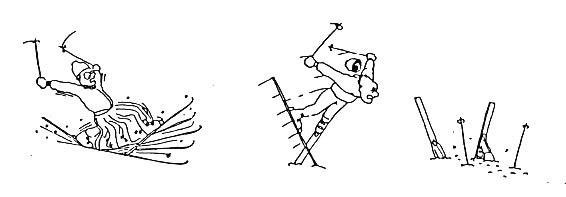

What do you think about these two ways to cut a tree?

One person is working hard, but isn't

getting much done.

The other is working smart, using an

effective tool, and is getting results!

Which kind of worker do you want to be?

Without proper tools, you'll often experience failure and frustration.

With good tools, you'll feel the thrill of success and satisfaction.

Your confidence will increase, and you'll look forward to the challenge

of solving new problems.

Some tools are physical, like a power

saw. Other tools are mental, like creativity and logic, curiosity

and enthusiasm, perseverance and flexibility, concepts and strategies, attitudes

and habits.

Where do you find these mental tools?

You know many already, you'll learn some from teachers and colleagues, and

others you'll discover for yourself. The goal of this website is to

help you develop powerful strategies and skills for problem solving, especially

in the fields of design, science, and education.

The following true stories about myself

(a skier) and my friend (a welder) illustrate essential principles for learning.

cartoons by Frank Clark

Learning from Mistakes (how I didn't

learn to ski)

My first day of skiing!

I'm excited, but the rental skis worry me. They look much too long,

maybe uncontrollable? On the slope, fears come true quickly and I've

lost control, roaring down the slope yelling "Get out of my way!

I can't stop!" But soon I do stop -- flying through the air sideways,

a floundering spin, a mighty bellyflop into icy snow. My boot bindings

grip like claws that won't release their captive, and the impact twists

my body into a painful pretzel. Several zoom-and-crash cycles later

I'm dazed, in a motionless heap at the foot of the mountain, wondering what

I'm doing, why, and if I dare to try again.

Even the ropetow brings disaster.

I fall down and wallow in the snow, pinned in place by my huge skis, and

the embarrassing dogpile begins, as skiers coming up the ropetow are, like

dominoes in a line, toppled by my sprawling carcass. Gosh, it sure

is fun to ski.

With time, some things improve.

After the first humorous (for onlookers) and terrifying (for me) trip down

the mountain, my bindings are adjusted so I can bellyflop safely.

And I develop a strategy of "leap and hit the ground rolling"

to minimize ropetow humiliation. But my skiing doesn't get much better

so -- wet and cold, tired and discouraged -- I retreat to the safety of

the lodge.

The break is wonderful, just what I need

for recovery. An hour later, after a nutritious lunch topped off with

tasty hot chocolate, I'm sitting near the fireplace in warm dry clothes,

feeling happy and adventurous again. A friend tells me about

another slope, one that can be reached by chairlift, and I decide to

"go for it."

This time the ride up the mountain is

exhilarating. Instead of causing a ropetow domino dogpile, the lift

carries me high above the earth like a great soaring bird. Soon, racing

down the hill, I dare to experiment -- and the new experience inspires an

insight! If I press my ski edges against the snow a certain way, they

"dig in." This, combined with unweighting (a jump-a-little

and swing-the-skis-around foot movement) produces a crude parallel turn

that lets me zig-zag down the slope in control, without runaway speed, and

suddenly I can ski!

Continuing practice now brings rapidly

improving skill, and by day's end I'm feeling great. I still fall

down some, but I'm learning from everything that happens, both good and

bad. And I have the confident hope that even better downhill runs

await me in the future. Skiing has become fun!

This experience illustrates two important

principles:

1) INSIGHT AND QUALITY PRACTICE:

I learned how to ski by doing it correctly, with high-quality practice,

not by making mistakes. There was no amazing improvement until I discovered

the tool for turning. This insight made my practicing effective so

I could quickly develop improved skill: insight --> quality practice

--> skill. Working as cooperative partners, insight and practice

are a great team. Together, they're much better than either by itself.

2) PERSEVERANCE AND FLEXIBILITY:

My morning ski runs weren't fun and I didn't learn much, but I kept trying

anyway, despite the risk of injury to body and pride. Eventually this

perseverance paid off. Because I refused to quit in response to frustrating

morning failures, I experienced the great joys of afternoon success.

/ But if I had continued practicing the old techniques over

and over, I never would have learned the new way to turn. Perseverance

led to opportunities for additional experience, but flexibility allowed

the new experience that produced insight and improvement.

Perseverance and flexibility are contrasting

virtues, a complementary pair whose optimal balancing depends on aware understanding

(both personal and external) and wise decisions. In each situation

you can ask, "Do I want to continue in the same direction or change

course?" Sometimes tenacious hard work is needed, and perseverance

is rewarded. Or it may be wise to be flexible, to recognize that what

you've been doing may not be the best approach and it's time to try something

new.

Learning from Experience

One of the most powerful master skills

is knowing how to learn. The ability to learn can itself be

learned, as illustrated by a friend who, in his younger days, had an interesting

strategy for work and play. He worked for awhile at a high-paying

job and saved money, then took a vacation. He was free to wake when

he wanted, read a book, hang out at a coffee shop, go for a walk, or travel

to faraway places by hopping on a plane or driving away in his car.

Usually, employers want workers committed

to long-term stability, so why did they tolerate his unusual behavior?

He was reliable, always showed up on time, and gave them a month's notice

before departing. But the main reason for their acceptance was the

quality of his work. He was one of the best welders in the city, performing

a valuable service that was in high demand and doing it well. He could

audition for a job, saying "give me a really tough welding challenge

and I'll show you how good I am." They did, he did, and they

hired him.

How did he become such a good welder?

He had "learned how to learn" by following the wise advice of

his teacher: Every time you do a welding job, do it better than the time

before (by learning from the past and concentrating in the present) and

always be alertly aware of what you're doing now so you can do it better

the next time (learning from the present to prepare for the future).

This is a good way to improve the quality of whatever you do. Always

ask, "What have I learned in the past that will help me now, and what

can I learn now that will help me in the future?", while concentrating

on quality of action in the present.

Steps and Leaps

In many areas of life, much

of your improvement will come one step at a time. Each step you take

will prepare you for the next step as you make slow, steady progress.

But you can also travel in leaps. This is possible because many skills

are interdependent, which is bad news (if you haven't yet mastered an important

tool, everything you do suffers from this weakness) and good news (because

key insights can let you make rapid progress, as in my skiing experience).

If you consistently learn from experience

by searching for insights, your steps and leaps will soon produce a wonderful

transformation. You will find, increasingly often, that challenges

which earlier seemed impossible are becoming things you can now do with

ease.

http://www.sit.wisc.edu/~crusbult/methods/ski.htm

copyright 2000 by Craig Rusbult

cartoons, copyright 1989 by Frank Clark