Videos and Web-Pages

for Chord Progressions

The web has many educational resources — to hear & see in audio-visual videos, and to read & see in web-pages — that can help you learn more about Strategies for Making Melodies during Chord Progressions and for Using Functional Harmony in Chord Progressions plus other musical topics. { also, the distinctive benefits of videos & web-pages and why I recommend learning from both. }

Strategies for Making Melodies

What? These melody-making strategies are the focus of my pages to help you improvise harmonious melodies with a colorized keyboard that uses red-blue-green to show the notes of three main chords.

How? A fun-and-effective way to learn is by using videos that teach melody-making strategies – the same ones I teach, so they're our strategies – and illustrate the strategies with example-melodies. Many excellent videos (graciously shared by skilled music teachers) are available, including these:

• make melodies by using arpeggios & scales (with music from Trinity College London, 1:32).

• creatively invent-and-develop musical motifs (Maybe 4 Notes is All You Need by Aimee Nolte, 17:48).

• Corey Congilio (in conversation with Rhett Shull, re: How Pros Play Blues) explains – from 4:30 to 7:30 of 18:11 – the artistic benefits of thoughtful choosing instead of mindless noodling.

• for explaining & illustrating a variety of melody-making strategies, one of my favorites is a Beginner's Guide to Jazz Improvisation by Julian Bradley, 18:15.

• the pros and cons of Arpeggio Soloing & Scale Soloing by Anthony Couch, 13:10.

• although I sometimes find it useful to “think classical” while playing white notes as passing notes, and “think blues” while also mixing in black notes, there is a “thinking classical” feel in some melodies with black notes, as in the Chromatic Melodies of Chris Houston. Or in “thinking popular” songs like Joyce's 71st Regiment March & Paper Mansions and Sophisticated Lady.

• the “tendency principles” of functional harmony (explained below) can guide a designing of melodies, as described – with visual analogy to pulling by dogs! – in four videos (5:05 total) by 8-Bit Music Theory.

• and more, eventually.

Functional Harmony in Chord Progressions

People enjoy two kinds of harmony, when we hear notes being played simultaneously in a chord, and we remember the notes being played sequentially in a melody. Both harmonies are combined in the satisfying “full music” of songs (in pop, rock, jazz, classical,...) that use chord progressions. The principles of functional harmony help us understand how to design progressions (with sequences of chords) that are interesting & enjoyable. I think the videos are especially useful for understanding music (in music theory) and for playing music. { If you want to play along with common chord progressions (CP's), an easy way is to use backing tracks. }

Most of what I know about functional harmony – to just understand CP's, or to also design CP's (and improvise melodies during CP's) – has been learned from web-pages (like these) and from videos like those below. They will be educationally useful for all musicians, including those who use my colorizing system — with red,blue,green showing the triad-notes of 6 diatonic chords (3 major, 3 minor) — with the colors designed to help a player improvise melodies during chord progressions. / The six diatonic chords are (I, ii, iii, IV, V, vi); capitalized chords (I, IV, V) are major, and lower-case chords (ii, iii, vi) are minor.

Two videos – explaining the essential ideas in functional harmony* – are given to us (thank you!) by Ian O'Donnell (7:59), and by Greg Dalessio (16:00) who covers a wide range of key concepts, ranging from human psychoacoustics (for understanding harmony) to the musically-logical organizing of chord progressions (using principles of functional harmony) that form the harmonic foundation for almost all of the music we hear.

Here is one way to summarize functional harmony:

In a major key, the diatonic chords (I, ii, iii, IV, V, vi, vii°) have harmonic functions when they're used as a tonic chord (usually I but also vi, and occasionally iii) or subdominant chord (usually IV but also ii) or dominant chord (usually V, very rarely vii°). Why do we define chords in this way? Because it's a useful way to think about music when we want to create artistic mystery — with a skillful blending of “predictability and surprise” that makes music interesting & enjoyable — by producing tension and then resolving tension, because we can do this by using the principles of functional harmony. What? In chord progressions, here are common tendencies: a tonic chord can move to subdominant or dominant; a subdominant often moves to dominant, but also to tonic; a dominant usually moves to tonic but not always.

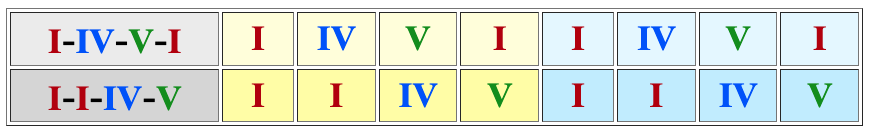

For example, harmonic tension leading to harmonic resolution occurs in a functionally designed chord progression that begins at rest (comfortably “at home” with minimal tension) when we're hearing a Tonic Chord, and then moves to moderate tension with a Subdominant Chord, then onward to high tension with a Dominant Chord, and to “resolve this tension” we move back to a Tonic Chord. This sequence-of-functions (Tonic ➞ Subdominant ➞ Dominant ➞ Tonic, as in I-IV-V-I or vi-ii-V-I ) is one “functional progression” that resolves to the Tonic, but musicians also use other functional sequences. By creatively using or's (with chord substitutions) and but's (with different functional sequences), musicians can invent a wide variety of chord progressions with artistic harmonies that serve as a framework for making artistic melodies & rhythms. For example, here is a creatively-logical developing – by first using but, and then or – of...

seven related chord progressions:

A harmonic resolution “from V to I” occurs at the end of I-IV-V-I. / This 4-chord progression can be “time shifted” as shown in these 8-bar sections, with the lower CP time-shifted rightward by one bar so its 4-bar sections end with V instead of I .

In this way I-IV-V-I becomes I-I-IV-V (with a different functional sequence) that can be repeated in cycles (so it's I-I-IV-V-I-I-IV-V-I...) and a resolution “from V to I” begins the next cycle of 4 chords, I-I-IV-V. Both timings, with V-to-I at the end or beginning, produce a functionally-satisfactory harmonic resolution. / Then with a chord substitution, by replacing I with vi (it's another tonic-function chord so the basic functional sequence remains the same) the I-I-IV-V becomes I-vi-IV-V (The 50s Progression) that — with another chord substitution, replacing one subdominant chord with another, thus maintaining the functional sequence — becomes I-vi-ii-V, and this (with time-shifting) becomes vi-ii-V-I (a Circle-of-Fifths Progression, e.g. it's Am-Dm-G-C in the Key of C). And pruning this produces ii-V-I , the most common progression in jazz.

These six CP's are closely related, like siblings or close cousins. All can be connected by modifying the functional sequence (with time-shifting or chord-deleting) or with chord substitutions that often don't change the functionality; and each CP has a V-to-I resolution. The seventh CP is a more-distant cousin, but still is related by the principles of functional harmony. Instead of time-shifting or chord-cutting, musicians change the functional sequence by rearranging the chords of I-vi-IV-V into I-V-vi-IV. When playing it, instead of one “BIG resolution” by moving from dominant V (high tension) to tonic I (low tension), there are two “medium-big resolutions” from dominant V (high tension) to tonic vi (semi-low tension) and then from subdominant IV (moderate tension) to tonic I (low tension). { comparing the “roller coaster” journeys }

All of these seven CP's are among our...

popular Chord Progressions:

Most songs (in folk, pop, rock, jazz, classical,...) have a harmonic structure — you can “hear the structure” in their sequential progression of chords — that is built on the foundation of three major chords ( I, IV, V ) that are featured when playing in a key, with key defined as "the main group of notes that form the harmonic foundation of a piece of music." Some CP's use only these major chords, and other CP's also include the key's minor chords, or other chords. We'll begin with...

popular progressions that use only Major Chords

simple progressions: Some four-bar CP's with only “the three major chords” are I-IV-V-I and I-I-IV-V, I-IV-I-V, I-IV-V-IV & I-V-IV-V, IV-I-V-V. And there are others. { explanations & examples from David Bennett } / Although most of these don't end with a resolution-to-I, you could do this IF you want (but usually you won't) in two 4-bar sections, as in “ -I-IV-V-I” where " " is any other CP, like “I-IV-I-V-I-IV-V-I”.

12-Bar Blues: The basic form is..... [[ iou – to be continued during mid-March 2025, with a condensing-and-revising of these ideas. ]] { explanations-and-examples plus backing tracks }

popular progressions that also use a Minor Chord

All of these are commonly played, and they're related in ways that are interesting & musically useful. Five of them (plus another) are musically interconnected when I-I-IV-V becomes (with a chord substitution) I-vi-IV-V and then (with another chord substitution) I-vi-ii-V and (with time-shifting) vi-ii-V-I and finally (with chord-pruning) ii-V-I . We'll begin by looking at...

I-vi-IV-V, the 50's Progression: Why does it sound so good? Here are three reasons. First, there is a continual increasing of harmonic tension. David Bennett describes it as "a perfect little journey away from the tonic, back to the tonic," with progressive increasing of tension from I (low) to vi (semi-low) to IV (medium) to V (high) and then, to begin the next loop of chords, back to I (low). Second, this 4-chord journey has smooth-sounding transitions — due to common tones that you can discover by comparing notes in the first three chords — plus the shifting of tonality from major to minor to major. The progression is musically logical with smooth transitions, mixes major with minor, sounds beautiful, is musically interesting. { explanations-and-examples plus backing tracks }

I-vi-ii-V and vi-ii-V-I : These are musically related to each other, and to I-vi-IV-V and ii-V-I. The "sounds" of I-vi-IV-V and I-vi-ii-V are similar (because IV and ii are both functionally equivalent subdominants) yet are different (because ii doubles “the minor sound” in the major key); and because I-vi-ii-V is a Circle of Fifths Progression, with each chord being “the 5th” of the following chord (as in the V-to-I resolution). It's easier to recognize The Circle when it's time-shifted into vi-ii-V-I that is Am-Dm-G-C (4/12 of the whole Circle of Fifths) in The Key of C. { explanations-and-examples plus backing tracks } / Because it's useful for the transitions-between-keys that's a central part of their art, jazz musicians often play “the circle” with vi-ii-V-I – and occasionally a longer iii-vi-ii-V-I – or the shorter...

ii-V-I : The progression of 251 is used in many kinds of music, but especially in jazz where it's the most frequently played CP, with many variations. It's like vi-ii-V-I but is shortened by removing vi, making it more useful for the quick changing-of-keys that often occur in jazz, using harmonies (why?) in The Circle of Fifths. { explanations-and-examples for The Circle and 251, plus backing tracks }

I-V-vi-IV: As described earlier, the six other CP's have one “big resolution of tension” with V-to-I (it was called an authentic cadence in classical music, and also now in pop-rock-jazz); but I-V-vi-IV has two “medium-big resolutions of tension” with V-to-vi (a deceptive cadence) and IV-to-I (a plagal cadence). If (as David Bennett says) I-vi-IV-V is "a perfect little journey away from the tonic," the I-V-vi-IV is two mini-journeys. Or you can imagine a roller coaster with I-vi-IV-V being the initial slow Big Climb (to top) followed by a Big Drop (to bottom), contrasted with I-V-vi-IV that has two Smaller Drops. For example, if we estimate — very roughly, and not to be taken literally — the levels of tension in I-vi-IV-V as (1-2-3-4-1....), the changes are (+1, +1, +1, –3). But in I-V-vi-IV the levels are (1-4-2-3-1....) and the changes are (+3, –2, +1, –2). These two “coaster journeys” differ in contour, offering different opportunities when we make music, and different experiences when we hear music. Both are useful ways to creatively invent music that is interesting and enjoyable. / [[ iou – In mid-September, I'll summarize these cadences (perfect, deceptive, plagal) and will link to Wikipedia & other pages, regarding their uses for functional harmony in classical music & pop-rock-jazz music) ]] { explanations-and-examples plus backing tracks }

[[ iou – during mid-September I'll write concluding paragraphs about our strategies for modifiying looped CP's (by time-shifting, chord-substituting, rearranging) or using non-looped CP's, plus changing chords more often, modifying chords to make them more complex, using chord inversions,... / and how CP's are among the many ways we can make a wide variety of interesting music. ]]

[[ and somewhere in the page I'll briefly describe the "dual functionalities" of vi/vi and iii/iii because each chord (vi and iii) shares two common tones with two other chords, with I and I, but also with IV and V. ]]

videos about Functional Harmony in Chord Progressions:

When you've built a strong foundation of knowledge about functional harmony, you'll more fully appreciate its uses in constructing chord progressions, as explained in the videos of other teachers.

I think you'll enjoy the ideas & music of Ayla Tesler-Mabe, who (in 17:58) logically explains & artistically illustrates important “influences” that have affected popular music, with 7 Chord Progressions That Changed Music History: her “7 CP's” are 4 common CP's — 145 (simple & blues), 1465 (50s), 1564 (popular), and 251 (jazz) — plus creative variations that are illustrated by Across the Universe (John Lennon), Warmth of the Sun (Brian Wilson), and Golden Lady (Stevie Wonder).

And other teachers have made high-quality videos, including many from...

David Bennett (videos about Chord Progressions)

I encourage you to learn from – and enjoy – the skillfully produced videos of David Bennett, who combines clear explanations with short musical examples (and visuals) from many popular songs plus his own playing, with expert production in putting it all together. He shows us why popular chord progressions (CP's) “work well” for making music that's interesting-and-enjoyable. He has a long playlist that includes 7 CP's – 6 CPs – 5 CPs – 4 CPs – and 27 other videos. When you click "more" in a video's description, you'll see the time each CP begins, if you want to choose. Or use my links — for each CP you can “Open Link in New Tab” and then view the tabs in order — to see the video-segments for each category of CP:

simple: I-IV-I-V — I-V-IV-V — I-IV-V-IV — IV-I-V .

12-Bar Blues: 111144115411 (it's the basic structure without a turnaround).

1645 (50s) — I-vi-IV-V (50's) plus 31 seconds for the “Blue Moon Progression” of I-vi-ii-V that is closely related (it replaces IV with ii, but both chords have subdominant function, and is analyzed below) — IV-V-I-vi (same as 50's, but time-shifted) — 50s Progression "as is" but with modified chords, for 5 Levels of Complexity —/— I-ii-IV-V (like 50s but with 2 measures of tonic ➞ 2 measures of subdominant, I-vi-IV-V ➞ I-ii-IV-V )

1564 — I-V-vi-IV (aka 1564) and vi-IV-I-V (by time-shifting 1564 into ...15641564...) — IV-I-V-vi (another time-shifted 1564) — {asking “when did it become so popular?” and using data to analyze-answer } —/— I-V-ii-IV (is like 1564, but vi is replaced by ii with a change of function) —/— I-IV-vi-V is like 1564 but swapping positions of V and IV so I-vi-IV-V ➞ I-IV-vi-V.

1625 and 6251 — both versions are analyzed to show how 1625 is “almost 50s (1645)” but now three of its changes follow the Circle of Fifths, which is easier to see in the time-shifted 6251 (it's Am-Dm-G-C in Key of C) that can be shortened to get...

251 (jazz) — I recommend starting with Charles Cornell (14:16) followed by David Bennett (17:39, strongly emphasizing its usefulness for changing the key) and Julian Bradley (12:49).

Circle Progressions — after an overview by Brad Harrison (in 11:20), David Bennett (15:29) begins with Am-Dm-G-C-F-Bº-E-Am to illustrate how a Circle of Fifths Progression (like 6251 & 251 but longer) can be designed so it fits into only 8 bars (not traveling the full circle of 12 keys) because it uses B° (a diminished chord) to “break The Circle” between F and E — also, I-bIII-bVII-IV (it's C-Eb-Bb-F in Key of C) travels “the other direction” (clockwise) with a Circle of Fourths — and Julian Bradley (in 14:34) explains The Circle in the context of jazz. {more about The Circle of Fifths}

progressions with bVII and/or bVI — DB describes many CP's with a flatted-seven chord (bVII) – that in The Circle are a “nearest neighbor” of IV – beginning with i-bVII-bVI-V (Andalusian Cadence) and the related I-bVII-bVI-bVII (Aeolian Vamp) — I-bVII-IV-I (Mixolydian Vamp) — I-bVII-V-bVI — I-V-bVII-IV —/— and with other chords but without bVII, i-bVI-V (Harmonic Minor Vamp) — I-bII (Phrygian Vamp) — i-IV (Dorian Vamp).

other CP's — Pachelbel's Canon Progression (I-V-vi-iii-IV-I-IV-V), concluding with how it influenced the looping-of-progressions in modern popular music — Descending Stepwise CP's — and many others in his playlist.

iou – During mid-September I'll be linking to additional videos from other teachers, for making melodies (certainly) and (maybe) for understanding chord progressions. Here are some possible videos about...

Strategies for Making Melodies:

The Circle of Fifths

[[ iou – During mid-September I'll summarize this important concept (it's useful for thinking about music and making music) by condensing ideas from here. ]]

Song Forms

[[ iou – during mid-September I'll develop this section to describe levels of structure, with bars (usually 4 beats, occasionally 3), then 4 bars (16 beats) or 8 bars, or 32 bars with AABA structure, plus chorus, verse, bridge, intro & outro,... / I'll connect this with changes of harmonic structure, e.g. changing from one kind of CP to another kind, during different parts of a structure; or changing the key, or its melody-theme(s), or... -- all of these are more of the many ways musicians can make a wide variety of music. ]] links: Master Class - and more, soon.

[[ iou – Eventually there will be other sections – mainly with links to videos – between what's above and below. ]]

In this LIGHT GRAY BOX, I examine applications & extensions of basic concepts. Common Tones and Neighbor Tones These valuable Strategies for Making Chord Progressions will be illustrated with the 50s Progression, to show how musicians use... common tones in chord progressions: When two chords share common notes (aka common tones) these notes produce smoother transitions between the chords during a progression. For example, the 50s Progression (I-vi-IV-V) has two common notes in each of its first two chord changes. In the Key of C, the changes are from C (C-E-G) to Am (A-C-E), and Am (A-C-E) to F (F-A-C), with C (the key's “home note”) in all three chords. These common notes produce two “smooth-sounding transitions” but with the tonality shifting from major to minor, then back to major. This combination of smooth transitions (due to shared common tones) and shifting tonality (major to minor to major) produces a progression that sounds beautiful, is musically interesting. { common tones in functional harmony } neighbor tones in chord progressions: As described above, a 50s Progression has two common tones in each of its first two chord changes, from C to Am, and Am to F. This is followed by a change from F (F-A-C) to G (G-B-D) with no common notes; instead each chord-note moves up two semitones, in parallel movements. Finally a harmonic resolution occurs when – to begin the next cycle of 4 chords – the G (G-B-D) goes back to C (C-E-G), with two “neighbor-note shifts” — especially B moving up to C (by 1 semitone), but also a weaker shift of D moving up to E (2 semitones) — while G is a common note in both chords. Another way to use neighbor tones is with... 7th Chords in chord progressions: Musicians often convert a dominant V into a 7th chord by adding a flatted-7th. Why? Because this adds some dissonance to the dominant triad (producing artistic mystery), and it makes the resolution of V7-to-I more dramatic. How? With a G7 (G-B-D-F) to C (C-E-G) you get an additional strong neighbor-note shift of one semitone (the usual B up to C, plus F down to E). The G7 also has a dissonant tritone (the 6 semitones between F and B) that is eliminated, that doesn't occur in C after G7-to-C. / A chord progression often includes a movement of subdominant-to-dominant, and during this move there is a common tone when moving from F (F-A-C) to G7 (G-B-D-F) with the 7 of G7, but not when G has only the triad notes (G-B-D) common tones for functional harmony: In addition to producing smooth transitions between chords, shared common tones are important for producing the functions of chords in a progression. The main dominant chord of C (C-E-G) shares two common notes with each of the other tonic chords, the Am (A-C-E) and Em (E-G-B); the subdominant chords of F (F-A-C) and Dm (D-F-A) also share two common notes, and so do the dominant chords of G (G-B-D) and B° (B-D-F). / But chords with different functions also can share notes,* as in the vi-IV — when moving from Am (A-C-E) to F (F-A-C) — that is used in the two most common progressions of modern popular music, I-vi-IV-V (50s) and I-V-vi-IV (1564). This combination of contrasts – by using the same notes in chords with different functions – is one reason for the popularity of vi-IV in these two progressions, along with the contrast of tonalities when major I is followed by minor vi and then major IV. [[ iou – * This "also can share notes" raises questions about the functionality of vi -- should we consider it to be only-tonic? or either tonic or subdominant depending on the context? or having dual functionality, e.g. during a 50s Progression it's vi to produce a smooth I-vi, but is vi for a smooth vi-IV ? Maybe. I'll learn more about this, then will summarize and make links. ]] common tones producing dual functions: [[ iou – this is an initial rough-draft version, and in mid-September the previous paragraph also will be revised to include some of these ideas ---- As explained above when analyzing the 50s Progression, vi shares two common notes with I and also with IV, so although overviews of functional harmony define vi and IV as being chords with different functions, in some ways, in some contexts we can view them as having similar functions. And yes, this kind of “dual functionality” is recognized in standard music theory. / during late August, I'll link to pages (Wikipedia + others) for these ideas about vi-chords, and will explain how iii (e.g. EGB, EGB) also shares common notes with two chords – with I (CEG) and with V (GBD) – so it also can have dual functionality; therefore, two dual-function chords are vi/vi and iii/iii. ]] [[ some possible links: (diagram) ("weak pre-dominant") (and a questionable claim that vi usually is considered subdominant - ??) ]]

[[ iou – Eventually there will be other sections – mainly with links to videos – between what's above and below. ]] using chord inversions in a chord progression spoiler alert: If you want to do your own “discovery learning” — by exploring possibilities, so you can discover principles & examples by yourself — first do this section and then continue reading. multiple factors in a chord progression: The two main factors that affect “the sound and feeling” occur when you define the CP by... • selecting its chords, as in I-I-IV-V (with only major chords) or (by adding a minor chord) I-vi-IV-V, and • sequencing the chords, as in I-vi-IV-V or (with same chords but different sequencing) I-V-vi-IV, to produce different CP's. / But the same CP will have a different sound-and-feeling when it's played in different ways, when you modify... • the tempo of chord changes, and rhythms of playing chords; the arrangement for “who does what” in a group – e.g. combining actions by chord-player(s) and bassline-player(s) – to produce the total harmony; • the inversions used for playing chords, as illustrated in these... examples of using chord inversions: If you're playing I-IV-V-I in the Key of C (so it's C-F-G-C), with available notes being (CDEFGABcdefg), one option is to play the CP “spread out” – using only one kind of inversion – as “CEG__FAc__GBd__ceg__”, where "__" shows that each chord (CEG, FAc,...) is held for awhile so you can hear “the sound” of each chord, and of the overall progression. Another way-to-play is “clustered together” – using different kinds of inversions – as “CEG__CFA__DGB__EGc__”. Play each way several times, and compare them. They sound very different — even though each is “the same CP”, is C-F-G-C, is I-IV-V-I — because inversions are one factor in producing “the sound” of a CP. opportunities for discovery learning: In addition to exploring chord inversions you can do experiments “with chords, without melodies” to make harmonious chords by using systematic strategies for experimenting to explore a wide variety of possibilities, with results summarized here.

Here I'm describing "the distinctive benefits of videos & web-pages, and why I recommend learning from both kinds of educational resources." Most hiqh-quality videos combine clear explanations with musical examples, for a combination of experiences that will improve your cognitive-and-functional knowledge of music, with knowledge that is cognitive (to understand music) and functional (to play music). How? Generally you can play music better when you know music better, with educational videos helping you know better. Specifically, your playing of music will improve when you also (in addition to videos for learning) use videos for playing along. / Videos can be time-efficient when used in either of two ways: when you totally focus on listening-and-watching, or when you do intelligent multi-tasking by listening while doing low-cognition tasks (preparing food, exercising, walking, working in the yard) so your mind is mostly-free to listen, think, and learn. And after multitasking, later you also can watch with focusing; sometimes “the visuals” are very useful (and/or enjoyable) for some videos, but with others you can get most of “what can be learned” by just listening. And high-quality web pages — like those I'm linking to, plus the parts of this page I'm writing — are time-efficient, with a high ratio of “amount learned / time invested” for high learning/minute. You can move at your own pace, reading-and-digesting the concepts to learn them thoroughly, to develop understandings that are deep and thorough. / I'll link to pages of other authors and also my Summary Page (with melody-making strategies) and Big Page (with more details) and its Introduction (about my colorized keyboard) and my original Big Page and a Chord Progressions Page with links to videos that are backing tracks – providing harmony and rhythm, but not melody – so you can “play along” by improvising new melodies, plus links to songs (with particular chord progressions) so you can play its old melody and improvise variations of the old melody. |

[[ iou – Eventually, maybe in late September, there will be other sections in the rest of this page, including other topics. ]]