Eternal Misery or Annihilation ?

When we ask “what will happen in hell? what will be the final result?”, three answers are Eternal Misery, Annihilation, and Reconciliation. This paper, written in 2000 and revised in 2010, carefully examines two of these views, and its main ideas are condensed into a 1-page summary. Both of these papers are also available in print-friendly pdf files, full-size (33 pages) and summary (1 page).

Since 2014, I've been writing a web-page that includes all three views, The Afterlife for Unbelievers - Will the final result be Eternal Misery, Annihilation, or Reconciliation?

A home-page provides an overview of what I've been writing about “what will happen in hell”.

Here is what you will find in this page:

Table of Contents (with links)

This paper — and everything else in the website asking "what will happen in hell?" — is...

Copyright

2000 by Craig Rusbult (with major revisions in 2010)

for the reader: I recommend beginning with Parts 1 and 2 — Gospel Fundamentals and What is Conditional Immortality* — and then you can read

Parts 3-6 in any order, supplemented (if you want) by corresponding sections in Part

7.

* What is Conditional Immortality? In 2014 when I re-examined Conditional Immortality (CI), I recognized that in this paper (written earlier, in 2010) I was using a logically-incorrect traditional definition. Why is it incorrect? Because, as explained in the next paragraph ("According to..."), CI actually includes both Annihilation and Reconciliation; CI is violated by only Eternal Misery, because it would require giving immortality to unsaved people, so it would violate The Condition ("if saved, then immortal") that defines Conditional Immortality. Therefore, the view that in this page is incorrectly labeled Conditional Immortality should be called Annihilation, if we want to be logical. I think it's useful to be logical, so in the page I'm currently developing (starting in 2014) the view is correctly labeled Annihilation, but in this unrevised "archived paper" — written in 2010 while I didn't understand the logic of CI — it still is called Conditional Immortality.

According to a theological doctrine of Conditional Immortality, “the gift of God is eternal life in Christ

Jesus our Lord” (Romans 6:23) and only people who fulfill the biblically stated

Condition — by accepting the grace of God offered through Jesus, so they are saved by God —

will receive the gift of eternal life. Those who reject the grace of God will not receive the gift of

immortality, and either (depending on what God decides) they will be Reconciled-and-Saved (so they satisfy The Condition and will be given Immortality by God) or they will be Annihilated (instead of being given Immortality). If their fate is Annihilation, following their biological death and a temporary resurrection

(to face a very unpleasant period of Judgment and Hell) their lives will come to

a permanent end. This

"eternally lasting death in

hell" differs from the "eternally lasting misery in hell" that is the fate of unsaved humans in a

doctrine of Eternal Misery. {a more detailed explanation of how we should define Conditional Immortality, and why}

Conditional Immortality or Eternal Misery?

1. Gospel Fundamentals:

Sin-and-Death and The Atonement

2. What is Conditional

Immortality? (the "2" is a link to Part 2)

3. Suffering and

Everlasting Punishment

3.1 — Suffering in Hell

3.2 — Everlasting

Punishment

4. Divine Justice and Mercy

4.1 — Infinite Punishing

for Finite Sins

4.2 — Universal

Salvation?

4.3 — The Overall Result

(does it seem fair?)

4.4 — Different Amounts

of Suffering

4.5 — Does God use

maximum persuasion?

5. Extra-Biblical

Influences on ideas about Immortality and Hell

5.1 — Our Goal:

Searching for Truth in the Bible

5.2 — Influences in the

Christian Community

5.2a — The Inertia of Tradition

5.2b

— Defending a Tradition

5.2c

— Improving People and Society

5.2d

— Personal Influences (external and internal)

5.3 — The Influence of Extra-Biblical Philosophies

5.4 — Coping With

Extra-Biblical Influences

6. Bible Passages often

claimed as support for Eternal Misery

6.1 — Matthew 25:31-46

(“eternal fire” & “eternal punishment”)

6.2 — Luke 16:19-31 (The

Rich Man “in torment” and Lazarus)

6.3 — Revelation 14:9-11

(“smoke ... rises for ever and ever”)

6.4 — Revelation 20:10

(“tormented... for ever and ever”)

7. Additional Ideas (to

supplement Parts 1-6)

7.1 — Conditional

Immortality in the Bible

7.1a — Bible-Information about Human Immortality

7.1b — Substitutionary Atonement with CI and EM

7.1c — Are humans created with an immortal soul?

7.1d — What is the ultimate result of hell-fire?

7.1e — Eternal Fire and Eternal Worms

7.1f — Life and Death on an Old Earth

7.1g — Does ‘death’ really mean death?

7.2 — Biblical Theology

with CI and EM

7.3 — Suffering and

Everlasting Punishment

7.31 — Suffering in Hell

7.32a — Everlasting Punishment by Everlasting Death

7.32b — What does ‘aionion’ mean?

7.4 — re: Divine Justice

and Mercy

7.41 — Infinite Punishing for Finite Sins

7.42

— Eternal Joy with knowledge of Eternal Misery?

7.43 — The Overall Result with CI and EM

7.44 — Is maximum punishing required for justice?

7.5 — Extra-Biblical

Influences on Our Views

7.6 — Important Verses

and the Big Picture

APPENDIX

You can read sections in the appendix in any order you want:

A. Soul

Immortality and Eternal Misery

A1 — Extra-Biblical

Influences for Bible Readers

A2 — How did EM become a

traditional doctrine?

A3 — Would

soul-immortality lead logically to EM?

A4 — Is soul-immortality

taught in the Old Testament?

A5 — What do ‘death’ and

‘destruction’ mean in the Bible?

B. Old and New Testaments, and Other Writings

B1 — Connections: Old

Testament and New Testament

B2 — The Purpose of

Sacrifices in the OT and NT

B3 — A ‘no denial’

argument for Eternal Misery

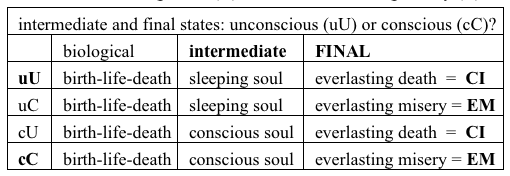

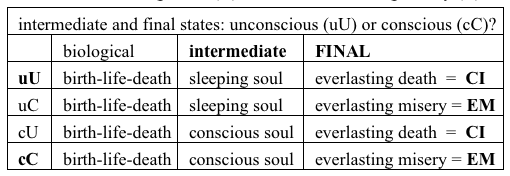

C. The Intermediate State: Asleep or Awake?

History of Salvation and

History of a Human

C1 — Does it matter if

we are asleep or awake?

C2 — Two Views of the

Intermediate State

C3 — Asleep or Awake:

What does the Bible say?

C4 — The Intermediate

State in Church History

C5 — How will God

re-create us in The Resurrection?

C6 — Emotional Appeal of

Continuing Consciousness

C7 — Paul’s Views of the

Intermediate State

C8 — Four Views of the

Intermediate-and-Final States

D. miscellaneous topics

D1 — Writing This Paper

(a personal history)

D2 — Universal Salvation

(is it desirable? biblical?)

D3 — How will Christians

be judged?

D4 — Is "guilt by

association" a logical argument?

D5 — The Logic of

Betting on Heaven and Hell

D6 — Does

sin-against-God justify infinite punishing?

D7 — Is maximum

punishing necessary for justice?

D8 — Edifying Attitudes by

Advocates of CI and EM

D9 — What does God’s

word say?

|

I'm an evangelical Christian who is theologically a

fundamentalist. Therefore, I think

our Christian beliefs should be based on the authority of the Bible, not the

authority of tradition. As you read

this paper, I encourage you to follow the example of the noble Bereans (Acts 17:11) who “examined the Scriptures every day

to see if what Paul said was true.” My examination of Biblical teaching begins, in Part 1, with the

essentials of Christian faith, with the fundamentals of The Good News. What is our problem, and what is the

solution offered by God?

1. fundamentals of The Gospel: Sin-and-Death and The Atonement

Jesus describes the death-to-life transformation of His

salvation: “For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son,

that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have everlasting life.”

(John 3:16; Bible quotations are from NIV, with italics added by me.

later I’ll make an HTML version with underlined passages that

link to BibleGateway where you can also look at other

translations: New American

Standard, Amplified, Young's Literal,...

The Problem: Our need for salvation (so we “shall not perish”) is explained in Genesis

2-3 beginning with Genesis 2:17 when God told Adam, “You must not eat from

the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, for when you eat of it you will

surely die.” After they sinned, when Eve and

Adam ate from the forbidden tree of knowledge, three bad things happened. The intrinsic result of

disobedience was a decrease in the quality of their relationship with God, described in Gen 3:7-11. Then two judicial penalties were decreed

by God, in Gen 3:14-24. First, a

decrease in quality of life, in Gen

3:14-19,23. Second, a death

penalty (Gen 3:22,24) when God removed the tree of life, thus causing a loss of

eternal life: “the Lord God said,

‘The man has now become like one of us, knowing good and evil. He

must not be allowed to reach out his hand and take also from the tree of life

and eat, and live forever.’ ... After he drove the man out, he placed on

the east side of the Garden of Eden cherubim and a flaming sword flashing back

and forth to guard the way to the tree of

life.” For the clearly

stated purpose of preventing disobedient

sinners from living forever, God removed the tree of life so they could not

“eat, and live forever.” When

the full supernatural protection provided

by God (symbolized by the "tree of life") was removed by God, Adam and Eve began to

perish, with natural processes temporarily allowing life while gradually

leading to their eventual death.

The Solution: Sin produced three results,

intrinsic (decrease in quality of relationship with God) and judicial (decrease

in quality of life, and loss of eternal life). The gift of full life (with

relationship, quality, and eternality) was offered to Adam, but was lost by his

sinful disobedience. Later, this

full gift (with relationship, quality, and eternality) was won back by the

sinless obedience of Jesus, and is offered to all who will accept God's gift of

grace. In this way the immortality

lost in Genesis returns in Revelation;

and then, as in Eden, it will be conditional: “To

him who overcomes, I will give the

right to eat from the tree of life, which is in the paradise of God. ... Blessed are those who wash their robes, that they may have the right to the

tree of life and may go through

the gates into the city. (Rev 2:7, 22:14)” Notice the connecting of “may

have” and “may go,” with “the right

to the tree of life” given to only those who also have permission to enter

heaven “through the gates into the city” because immortality is conditional, because God

gives eternal life to only those who will live with Him forever in

heaven.

Throughout the Bible, the focus of justice and salvation

is the contrast between death and life. In Genesis 3,

due to sin we earned the penalty of death

(decreed and allowed by God) when the tree of life was removed by God). In Genesis 22, the son of Abraham

is saved from death when God provides

a substitutionary sacrifice. In

Exodus 12, during the first Passover the blood of a sacrificed lamb

(symbolizing the Passover sacrifice of Jesus, in a foreshadowing of his death)

protects the first-born sons of the Hebrews from death. And in Old

Testament Law (in Leviticus,...) the penalty for serious sin-crimes is death, not long-term imprisonment with

suffering.

God’s method of salvation is the sacrificial death of Jesus, in a substitutionary atonement that lets us pass from death to life.

Jesus accepted our punishment (He died

in our place to satisfy the death

sentence decreed in Eden) and by his own sinless life (always obeying the

Father, as commanded in Genesis 2:17) He earned the right to make his own supernatural eternal life available, as

a gift of grace, to all who will accept.

In each key situation – Eden, Isaac, Passover, Law,

Substitutionary Atonement – the punishment that is earned (or avoided, or endured) is death, not

misery that never ends. On the

cross, Jesus accepted a penalty of death

for us; He did not accept a penalty

of eternal misery.

Consistent with these fundamentals, New Testament

writers often use terms clearly stating that, if there is no salvation by God,

the final fate of sinners will be death,

as in these statements by...

Jesus: “Whoever

believes in him shall not perish but

have everlasting life,” and “whoever

hears my word and believes him who sent me has eternal life and will not be condemned; he has crossed over from death to life.” (John 3:16, 5:24)

And in Luke 19:27, “Those enemies of mine who did not want me to be king

over them — bring them here and kill

them in front of me.”

Paul: “They know God's righteous decree that

those who do such things deserve death.” /

“All who sin apart from the law will also perish apart from the law.”

/ “The wages of sin is death, but the gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord.” (Romans 1:32, 2:8, 6:23)

James: “Sin, when it is full-grown, gives birth

to death.” “Whoever turns a sinner

from the error of his way will save him from death and cover over a multitude of sins.” (James 1:15, 5:20)

John: There is “a sin that leads to death.” (1 John 5:16-17)

These statements clearly state that the eventual fate

awaiting unsaved sinners is death. A doctrine of Eternal Misery requires an

unusual defining of death as eternal life in misery by retaining two

outcomes in Genesis 3 (loss of relationship and loss of life-quality) but

eliminating the third (loss of eternality). To avoid a conclusion

that "death = death", advocates of EM often claim that the death

in Genesis 3 (and throughout the Bible) is only Spiritual Death, not Physical

Death, even though God's purpose for removing the "tree of life" in

Genesis 3:22 was because sinners "must not be allowed to...live

forever." The judicial penalty

for sin is death.

But a defender of EM might claim that although human sinners

cannot live forever without “the tree of life” in natural biological life, we have immortal souls that will live

forever as a disembodied soul, or in

a supernatural resurrected body. Although this is possible, it is

speculative (with no support in the text) and is illogical when we ask an

important question: if God did not

want human sinners to live forever in their natural bodies, why would He want

sinners to live forever as disembodied souls or in supernatural bodies?

God is sovereign — He created our

natural bodies and our souls, and He will create our supernatural bodies, and

God controls all life — so if He wants a body or soul to be alive, it

will remain alive; and if He wants

any life to end, that will happen.

Therefore, our question is not "what can God do?" (there are no limits) but "what does the

Bible say that God will do?" When we look at all that is taught

in the Bible, the answer seems to be eternally lasting life for the saved, and

eternally lasting death for the unsaved.

An examination of

these ideas — and others, when we ask if "death due to

sin" provides support for a young earth (no) and if flammable materials

(weeds, trees,...) can survive hell-fire, and how a fire can burn

eternally — continues in Sections 7.1d-7.1e.

2. What is Conditional Immortality?

This section compares Conditional Immortality (CI) and

Eternal Misery (EM) so our evaluations can be based on accurate understanding.

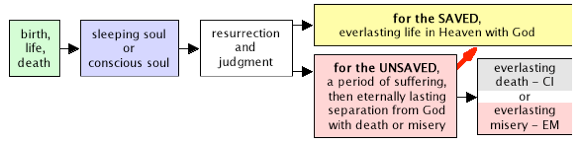

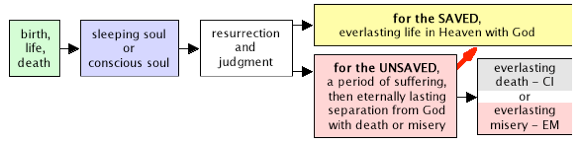

Conditional Immortality (CI) and Eternal Misery (EM) are

identical in almost every way; they

differ only in the final state of unsaved sinners. In the diagram below, 5 boxes are

identical for CI and EM. The only

difference (indicated by “or”) is the final state for unsaved people, for those who have not been saved through the grace

of God. With CI, everlasting death is

the punishment with an eternally lasting result, and their final state is non-existence. With EM, everlasting misery

is the eternally lasting punishment, and their final state is existence. In both CI and EM, unsaved sinners

suffer in Hell and are separated from God for all of eternity, by either

permanent death (in CI) or miserable exile (in EM).

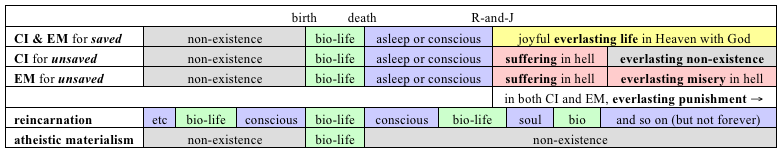

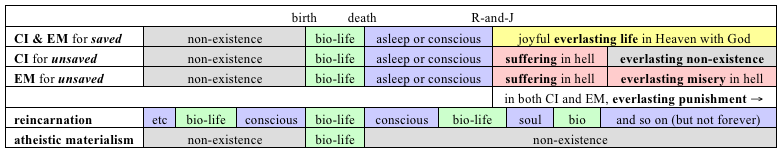

To help you understand the similarities-and-differences

between CI and EM, the table below shows 4 theories (2 Christian, and

2 non-Christian) about life experiences from before

conception-and-birth through Resurrection-and-Judgment (R-and-J) to

the Final State.

As indicated by “non-existence”

before birth, Christians believe that we have one biological life, so we did

not exist before our conception-and-birth.

By contrast, reincarnation

proposes that we live many times, in the past and future, with a conscious

intermediate state between our biological lives; reincarnation is discussed in Section

5.3.

Christians have two common views about the intermediate state between death and resurrection: as a time when the soul is asleep, or is conscious (which is basically pleasant for the saved, unpleasant

for the unsaved) but without a body. Either state is compatible with CI or

EM.

R-and-J: The

Resurrection of all people is described in Daniel 12:2, “multitudes who sleep in the dust of the earth will

awake,” and John 5:28, “a time is coming when all who are in their

graves will hear his voice and come out.” For unsaved sinners the divine Judgment and life in hell will be

unpleasant, with suffering that is psychological (with regrets over a missed

opportunity for eternal life) and maybe also physical.

CI and EM agree

that all humans will be resurrected so they can face divine judgment, and that

the saved (those who accept the

salvation graciously offered by God) will enjoy eternal life in heaven with

God, but the unsaved (who reject

salvation) will endure a period of suffering during judgment and in

hell. CI and EM disagree about the duration of

suffering — with CI it is temporary, with EM it is permanent.

A third Christian view, which is

symbolized by a red arrow on the diagram pointing from “a period of suffering”

to “in Heaven with God,” proposes (disagreeing with CI and EM) that after

Resurrection and Judgment, unsaved humans will have a chance to repent, and

some (perhaps all) will repent, will be saved by the grace of God, and will

receive the gift of eternal life in heaven. I call this view Second Chance Salvation, and if all

repent (which is the usual hope of its advocates) it becomes Universal Salvation or Universalism. This idea, which I think is inconsistent

with what the Bible teaches, is discussed in Section 4.2.

3. Suffering and Everlasting Punishment

Part 2 accurately describes

Conditional Immortality and Eternal Misery, so we can evaluate CI and EM based

on what they are.

Part 3 also aims for accuracy, by explaining that — in

contrast with an "all or nothing" claim that if hell is not eternally

lasting misery, there is no hell with suffering — CI is consistent with

biblical descriptions of hell.

According to Jesus, two consequences of hell are suffering and everlasting punishment.

We'll look at these two characteristics in Sections 3.1 and 3.2.

3.1 — Suffering in Hell

For unsaved humans, judgment and hell will be unpleasant:

Jesus says, “As the weeds are pulled

up and burned in the fire, so it will be at the end of the age. The Son of Man will send out his angels,

and they will weed out of his kingdom everything that causes sin and all who do

evil. They will throw them into the

fiery furnace, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth. (Matthew

13:40-43); throw that

worthless servant outside, into the darkness, where there will be weeping and

gnashing of teeth. (Matt 25:30)”

Similar descriptions are in Matthew 13:49-50 and 24:48-51.

With CI, a response of “weeping

and gnashing” is expected if resurrection

produces a mental-and-physical state that is extremely aware (more than in our

biological life) with a knowledge that the current judgment will be followed by temporary

suffering and then everlasting death. The contrast between this tragic

situation (for self) and the glories of joyous eternal life (for others) will

lead to a regretful remembering of missed opportunities, in the bio-life that

is past, to accept salvation and thus qualify for heaven. This state of mind — being

intensely aware and facing the ultimate human fear, the extinction of life

— will produce the powerful emotions that are described as sorrowful

“weeping and gnashing.” But the

Bible does not say how long this unpleasantness will endure, whether it will

last for awhile (as in CI) or forever (as in EM).

Some suffering would be caused by this psychological

response to the judgment-situation and the subsequent life in hell. There also might be some physical

pain; maybe this pain is actively

caused by God, or (more likely) God just establishes the hell-situation and then

takes a passive "hands off" approach and the situation

(including life without God) makes it very unpleasant. But all I can say is “might be...

maybe” since we don't know much about the details of hell. The Bible doesn't tell us much about

hell, so we should be cautious and humble in our speculations.

With either CI or EM, judgment-and-hell will be an

unpleasant experience, with suffering that is certainly psychological and maybe

also physical. The only difference

is between temporary suffering (CI) and eternal suffering (EM), but the Bible

never says how long the suffering will last. Therefore, passages that describe

suffering in hell do not provide support for EM, relative to CI.

3.2 — Everlasting Punishment

In Matthew 25:46, Jesus explains that some humans “will go

away to eternal punishment” where eternal punishment comes from the Greek kolasin aionion. This statement does not teach EM because

kolasin is a noun,

not a verb, so it is correctly

translated as punishment (a noun)

rather than punishing (a verb); with CI the eternally lasting death is a

punishment (the loss of existence)

that lasts forever, even though the punishing

(the suffering in hell, which occurs in both CI and EM, as explained above)

does not last forever.

That is the quick answer. The rest of this section looks at "punishment that is everlasting" in more detail.

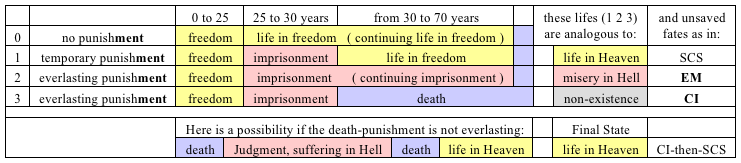

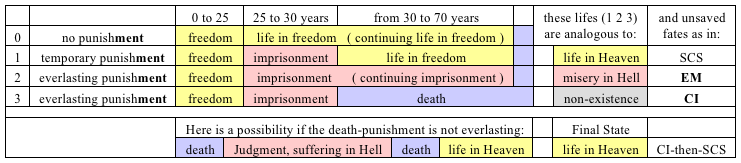

We'll begin by looking at three types of punishment used by humans, shown in

three rows (1, 2, 3) in the top-left part of this table:

This table has three related parts:

• The top-left part shows three

stages of life (from 0 to 25 years, 25 to 30 years, and 30 to 70 years) for

four imaginary people:

#0 lives his entire life in freedom with no judicial punishment, but #1 is imprisoned for 5 years and

is then released until he dies at 70,

#2 is imprisoned for his entire life, from 25 until he dies at 70, and

#3 is imprisoned for 5 years, then (in a death penalty) is executed. Their punishments, respectively, are

none, temporary, everlasting (lasting throughout the person's lifetime), and

everlasting. In either #2 or 3

the punishment is everlasting because there is never a time (after age 25) when

the person lives in freedom, by contrast with #1 where the temporary

punishment is non-everlasting.

• The table's right side shows that if the final stages of

bio-life (30-70 years) are converted to the similar post-resurrection Final States, the

human punishments (temporary imprisonment followed by a pardon, permanent

unpleasant imprisonment for life, and death penalty) are analogous to final

states with Second Chance Salvation (suffering, then life in heaven), Eternal Misery (suffering continues), Conditional Immortality

(suffering, then non-existence).

Hopefully, this concrete example (by thinking about the human

punishments in 1, 2, and 3) will help you see why the punishment does last

forever, as described in Matthew 25:46, with either EM or CI.

• The bottom row shows an imaginary situation where the

post-judgment death is not everlasting, in a scenario (that is not seriously

proposed by anyone) combining CI and SCS.

Why is this relevant?

Because Jesus knew that he would soon be showing us, by his own

resurrection, that a reversal of death is possible if God wants it to happen

and causes it. Therefore, he said “eternal punishment” to clarify that he

was not describing this scenario:

resurrection and judgment, temporary

death-punishment, then a divine pardon and re-resurrection to life in

Heaven. But in Matt 25:46 the

eternality of God’s death sentence is an argument against SCS, not against

CI.

In Matt 25:46 there is "parallel wording" for eternal punishment (kolasin

aionion)

and eternal life (zoen

aionion); we know that life for the saved will be

eternal, so will life for the unsaved also be eternal? This logic is valid, but only if

“punishment” means punishing, and if we also ignore other arguments throughout

this paper, including two other possible meanings of ‘aionion’

in Section 7.32b.

Does eternal joy depend on eternal misery, because if one does

not occur, neither does the other?

No. We should not conclude

that IF punishment (for the “cursed”)

is not eternal because there is no Eternal Misery, THEN life (for the “righteous”) will also not be eternal. Why?

First, there is a difference between a noun and verb, and

between life and death. As

explained above, kolasin

is a noun (not a verb) so it is correctly translated as punishment (a noun) instead of punishing (a verb); eternal punishing is a process that requires a conscious human who suffers

forever, but eternal punishment can

occur with a death that lasts forever. With life and death there is a

difference in process (being eternally alive is a process, but being eternally

dead is not) and this difference is consistent with the parallel wording, with

the reward (life) and punishment (death) both lasting forever; after resurrection and judgment, the

saved and unsaved will be alive forever and dead forever, respectively, with

both results being eternal.

Second, in addition to Matt 25:46 we see the promise of

eternal life in many other places, including Revelation 2:7 & 22:14

(through “the tree of life”) and 21:3-4 (“there will be no more death”), Luke

20:35-36 (we “can no longer die”), 1 Corinthians 15:42-57 (we will then be

“imperishable... with immortality” because “death has been swallowed up

in...victory through our Lord Jesus Christ”), 1 Timothy 1:16 (we will

“receive eternal life”). But

in each of these passages, and all other similar passages in the Bible,

the divine gift of immortality is conditional; in these passages it is for “him who

overcomes, ... those who wash their robes, ... his people, ... those who

are considered worthy, ... [who do] the work of the Lord,... who would believe

on him.” And when Jesus declares,

in John 10:27-28, that “I give them eternal life, and they shall never perish,”

this gift of eternality is only for “my sheep” who “listen to my voice” and

“follow me,” because “he who believes in me... will never die. (John 11:25-26)” And in John 17:2, Jesus praises

the Father who has “granted him [Jesus] authority over all people that he might

give eternal life to all those you have given him.” Because we believe in the resurrection of Jesus (who lives forever) we can be confident that believers who are “in Jesus” also will live forever. God’s promise of eternal life is

affirmed throughout the New Testament, over and over, not just in Matthew

25:46.

The if-then condition — IF

you overcome (wash your robes, are my person, are worthy, do my work,

believe, listen and follow), THEN you will be given immortality by God —

is important. Why? Because when unconditional immortality

is assumed, so all humans (including the unsaved, although they have not

overcome...) will live forever, everlasting punishment

cannot occur without an everlasting punishing

of the unsaved people who cannot die, and this is EM.

But a conclusion of EM is not

warranted, because an if-then conditionality is taught in the Bible,

where we find many verses clearly stating that saved humans will live forever,

and no verses clearly stating a corresponding immortality for unsaved

humans; instead, the fate of the

unsaved is usually described as death.

a review: If we

don't assume an unconditional immortality of all humans, and if we acknowledge

that kolasin

is a noun so we should think about everlasting punishment (a noun) instead of punishing (a verb), Matthew 25:46 does not provide logical support

for EM because eternal punishment (stated in the verse) does occur with

either CI or EM, even though eternal punishing (not in the verse) occurs only

with EM.

A discussion of Matthew 25:46

continues in Section 7.32a, and in 7.1e the scope widens to include “the

eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels” in Matthew 25:41. Section 7.32b has another

argument: “In case in case you’re

not persuaded by the "noun, not verb" argument for distinguishing

between punishment and punishing, the multiple potential meanings of ‘aionios’ may give you another reason to see the lack of

support for EM.”

4. Divine Justice and Mercy

In

writing Part 4, my goal is to defend the honor of God. Why do I think this is necessary? Because with a doctrine of Eternal Misery,

the character of God does not seem to match the God we see in the Bible, who is

severe in his judgment but is fair, who loves and forgives. The biblical picture of God

—severe yet fair in judgment, loving and forgiving — seems more

consistent with CI than with EM.

This should not be the deciding factor in deciding between CI and EM

— we should focus on what the Bible teaches, as in Parts 1-3 and 6, plus

7.1-7.3 — but it is something to consider.

4.1 — Infinite Punishing for Finite Sins

Based on our human sense of justice, most people (Christian

or not) think it isn't justified to make people suffer for an infinite time, as

in EM, to punish them for sins that were committed during a finite time during

their life on earth. Is EM

consistent with the principles of love and forgiveness taught in the

Bible? Jesus compared human vengeful justice (“an eye for an eye”) with the merciful justice of God, by telling us

to “Love your enemies, bless those who curse you, do good to those who hate

you, and pray for those who persecute you, that you may be sons of your Father

in heaven. He causes his sun to

rise on the evil and the good, and sends rain on the righteous and the

unrighteous. ... Be perfect,

therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect. (Matthew 6:44-45,48)” Here, Jesus tells us that God is more

merciful than we deserve. But with

EM, God seems to be much less merciful than we deserve.

It would be especially surprising if Eternal Misery is the

policy adopted by a God who is loving and forgiving, just and wise, if the

endless misery has no beneficial function, if there is no educational or

rehabilitative value, with no hope for improvement. And there will be no rehabilitation if

(as I think the Bible teaches) there is no "second chance" for

repentance and salvation, if those who reject God's grace during their natural

lifetime really are lost.

4.2 — Universal Salvation?

The main theme of Section 3.2 is that, with CI, hell is real and

it will be unpleasant for the unsaved. This section emphasizes the horror of

EM. By contrast with CI, where hell

is unpleasant but is not horrendous which (it seems to me) is the situation

with EM. Some readers think

CI is "too soft” because there is no everlasting misery, but others

think it is "too hard" because there is suffering and death,

so CI can get criticized from both directions.

The idea of Universal Salvation

(US), with God giving everyone a second chance for salvation, is

emotionally appealing, and I would join most people in voting "yes” for

this, if God asked us to decide.

But the Bible tells us what God has decided, and it doesn’t seem to be

universal salvation.

Here are examples of verses cited as biblical support for

US: Jesus says “I will draw all men to myself (John 12:32)”; “God has bound all men over

to disobedience so that he may have mercy on them all. (Romans

11:32)”; “in Christ

all will be made alive (1 Cor 15:22)”; “God was pleased to have all his

fullness dwell in him [Jesus Christ], and through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether things on earth or

things in heaven, by making peace through his blood, shed on the cross.

(Colossians 1:19)”

With CI, “all” really means all because all humans who remain alive have submitted their wills

to God, and love God, because all of the rebels (humans who say "my will

be done, not yours" and who do not love God and submit to Him) have been

eliminated by death. But with EM

these rebel-humans still exist, so the “all” is not really all.

The horror of EM-hell is a strong motivation for proposing

US. It’s also a motivation for

proposing CI, but there is a major difference; I think CI is strongly supported by

scripture and is clearly taught in the Bible, but US is not consistent with the

Bible. Although some verses (saying

“all”,...) seem to support US, these can be explained in other ways (especially

with CI, although it’s not as easy with EM) and there are many other verses

indicating that US is not the way it will be.

If an omnipotent God “wants all men to be saved and to come

to a knowledge of the truth (1 Tim 2:4),” nothing could prevent this from

happening. But here Paul is

describing God's desire (what He

wants to happen) rather than a fact (of

what actually will happen); these

can differ because God has given us freedom to disobey what He wants us to do,

and He respects our choices.

How will God judge those who

haven't heard the Gospel, or who are devoted to a religion (with an associated

deity) that is popular in their culture, or who are feeble-minded, or who die

when they're very young? I don't

know, but since God knows everything in our hearts and minds, He will be able

to judge fairly, to achieve justice.

We should be humble in our claims about who will and won’t

be saved, and why, because Jesus told us there will be surprises. Jesus did say that “no one comes to the

Father except through me,” but we don’t know all of God’s criteria for judging

people. For example, we cannot know

(in Romans 2) what “will take place on the day when God will judge men's

secrets through Jesus Christ,” especially for those “who do not have the law”

but “show that the requirements of the law are written on their hearts, their

consciences also bearing witness, and their thoughts now accusing, now even

defending them.” We don’t know what

is happening in the hearts-and-minds of people who outwardly seem to have

rejected the salvation offered by Christ (or seem to have accepted it) or when

it is too late for the vineyard workers in Matthew 20:1-16. And we cannot know with certainty who

will be unpleasantly shocked to discover that, as Jesus warns in Matt

7:13-27, “not everyone who says to me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ will enter the kingdom of

heaven, but only he who does the will of my Father who is in heaven.”

But even though we should be humble, as described above, we

should confidently proclaim what IS clearly stated in the Bible, and we should "live

by faith" by making decisions throughout each day on the basis of

trust in God's character, while obediently letting God’s commandments

guide our thoughts and actions.

[[ an update in 2021: The more I've learned about Universal Salvation (aka universal Ultimate Restoration) the more plausible it seems. I've learned a lot after writing this page in 2010, and now I'm still very confident that God will not cause Eternal Misery, but... I'm not confident in claiming that either "it will be Annihilation" or "it will be Restoration" because I think either outcome is biblically plausible. Either view can be believed-and-defended, based on what we see when we carefully study the Bible. / Beginning in 2014, I'm writing a page about my current views. It includes a major section describing the strong biblical support for Ultimate Restoration (UR) due to verses that support UR, plus reasons to question verses that superficially seem to de-support UR.

4.3 — The Overall Result (does it seem fair?)

For an individual in a world of CI or EM, what is the

overall change from beginning to end?

With CI, a person who accepts salvation goes from nothing,

before birth, to a temporary natural lifetime (with mixed pain and pleasure) to

a joyous eternal life in heaven. A

person who rejects salvation goes from nothing to a temporary natural lifetime

(mixed pain and pleasure) to judgment-with-suffering and the "nothing"

of non-existence. Thus the overall

result, from beginning to end, is either extremely positive (with salvation,

the change is nothing-to-joy) or neutral (without salvation, it’s

nothing-to-nothing).

With EM, a saved person still goes from nothing to extremely

positive (in joyous eternal life), but an unsaved person goes from nothing to

extremely negative (with eternal misery in hell).

If EM is true, the unsaved are BIG losers. For them the "gift of life" is

a heavy burden that, if they had the choice, they would have been wise to

refuse. But they had no choice.

By contrast, with CI there are winners but no losers. Those saved by the grace of God are big

winners with a wonderful life, as in EM. But for the unsaved, now their

treatment by God seems fair. They

go from nothing to life to judgment-and-consequences

to nothing. They have experiences (positive

and negative) during life and judgment, but their overall change, from nothing

to nothing, is neutral with no gain or loss.

A justifiable question, asked by an unsaved person

experiencing eternal misery in hell, would be “Why did you make me like this?

(Romans 9:20)” A traditional view

of EM-hell becomes even more difficult to justify, in terms of a human sense of

justice, with a mix (which is the doctrine of some major denominations) that

combines EM with the predestination implied by passages such as Romans 8:28-30 and

9:10-23. In Romans 9:20-23, Paul

says, “But who are you, O man, to talk back to God? Shall what is formed say to him who

formed it, ‘Why did you make me like this?’ Does not the potter have the right to

make out of the same lump of clay some pottery for noble purposes and some for

common use? What if God, choosing

to show his wrath and make his power known, bore with great patience the

objects of his wrath — prepared for destruction? What if he did this to make the riches

of his glory known to the objects of his mercy, whom he prepared in advance for

glory?” But doesn't it

seem reasonable — for a person who never asked to be born and is now

enduring eternal misery in hell, who never had a chance to choose whether to be

born, and then (if the predestination implied in Romans 9 is true) never had a

chance for salvation — to ask the God who is keeping him or her alive in

pain, “Why did you make me like this?”

But with a CI-hell and its "nothing to nothing" change, this

why-question is less justified, even with predestination. { Both CI & EM are

logically consistent with any view of free will, from full predestination to

total freedom, or anything in-between. }

note: Christians

who base their views on the Bible have a wide range of views about

predestination, from extreme Calvinism (with "double predestination"

of both saved and unsaved) through single predestination (with some "elected"

for salvation, while others can freely choose what they want), to no

predestination so every person is free to choose.

Some advocates of EM say,

"Those in hell get what they wanted.

If they want to live without God now, later they’ll get more of what

they want by living without God in hell." C.S. Lewis proposes this when he says,

“the damned are, in one sense, successful, rebels to the end; the doors of hell are locked on the

inside.” Usually I like the way

C.S. Lewis thinks and writes, but this idea seems illogical because a rebellious

desire for independence — refusing to submit to the will of God,

saying "I want my to live my life the way I want, without obeying God"

— is not the same as wanting independence from God during a misery-filled

eternity in hell. The first "I

want" (re: biological life on earth) does not lead to the second "I want"

(re: eternal life in hell).

There are two ways to "give

people what they want" if they reject a loving relationship with God: by an eternally miserable existence without God (as in EM) or an eternally lasting non-existence without God (as in CI). And maybe CI-hell will include a

temporary existence without God, and an unsaved person will realize how

unpleasant this is, between the beginning and ending of resurrection life.

EM also raises questions about

what God will do with humans who die in miscarriage or abortion, or who die

young or have a very low IQ so their "decisions about salvation" are

not made in a mature way. If life

begins at conception, and if immortality is unconditional and universal so

nobody who has been alive ever dies, are victims of abortion condemned to an EM-hell (this doesn't seem fair) or are they guaranteed

eternal life in heaven (so abortion will always produce an extremely good

overall result)? But with CI

there is a "nothing to nothing" possibility, so these dilemmas seem

less troublesome.

4.4 — Different Amounts of Suffering

According to a human sense of justice, differing amounts

of sin should lead to punishment with differing amounts of suffering. This human logical intuition is what we

also see in Scripture.

Jesus says, “That servant who knows his master's will and

does not get ready or does not do what his master wants will be beaten with

many blows. But the one who does

not know and does things deserving punishment

will be beaten with

few blows. From everyone who has been given much, much will

be demanded; and

from the one who has been entrusted with much, much more will be asked. (Luke 12:47-48)” And “it will be more bearable for

Sodom on the day of judgment than for you [who heard and rejected Jesus]. (Matt

11:24)” Here, the degree of

punishment for disobedient sinfulness (for “not doing what his master wants”)

depends on life-context, on a sinner's

knowledge (by “knowing his master's will”) plus his abilities-and-opportunities

(being “entrusted with much”).

For the unsaved, Jesus described unpleasant experiences

(mental and maybe also physical) beginning with Resurrection and the Final

Judgment. In CI, all who are

condemned have the same final result (death) but the intensity and duration of unpleasant experience can be varied if

God makes individually customized decisions about how much suffering is

justified and thus whether to prolong a life or, at a time He decides is

appropriate, to end it. But

with EM the only variable is intensity

of unpleasantness, since the duration will be eternal for everyone. Because CI involves two variables, not

just one as in EM, CI allows personally customized adjustments to produce

different amounts of punishment.

4.5 — Does God use maximum persuasion?

Consider the most important event in Christian history, the

resurrection of Jesus. If God had

wanted everyone to be certain, most doubts would have been erased if the risen

Jesus had marched through downtown Jerusalem, showing his hands, feet, and

side, while doing flashy miracles to clearly demonstrate His power. Why wasn't this done? The available evidence is

impressive — we have the testimony of many eyewitnesses whose lives were

dramatically changed, a lack of disproof (no dead body could be produced,...),

and more — but why is there no proof? There is enough evidence to warrant a

logical conclusion that "Jesus was physically resurrected," but the

evidence is not overwhelmingly decisive.

And why doesn't God convincingly persuade each of us, like

He did with Paul, by giving each of us a Damascus Road Experience (as in

Acts 9:1-22) with bright lights and a "voice from nowhere" followed

by three days of blindness and a miraculous healing?

I'm not sure, but perhaps a state of uncertainty is intended

by God, who seems to prefer a balance of evidence, with enough reason to

believe if we want to believe, but not enough to intellectually force a

believing against our will. Instead

of overpowering us with displays of obviously miraculous power until we

grudgingly give up and give in, God wants us to want to come to Him.

With a balance there is free choice, and the choice is made primarily

not by intellect, but by the heart and will.

A balance is also needed for

developing the living-by-faith character that is highly valued by God. Even though we live in a world of doubt,

God wants a total commitment from us, with true repentance followed by a

complete trust in God that is manifested in all thoughts and actions of daily

living.

A "balance between certainty and doubt" is good

for building, in believers, an ability to live by faith. But it hurts those who choose to not

believe, who (if EM is true) will suffer eternal misery, but who might have

believed if the balance of evidence had been shifted. With EM it seems that God should do

everything possible (by showing the risen Jesus to everyone in Jerusalem, doing

daily miracles, providing Damascus Road Experiences for everyone who needs it,

and so on) to be sure nobody goes to eternal misery in hell.

But with CI a nonbeliever goes from initial non-existence to

final non-existence; in between

there are experiences (some good, some bad) but the overall result, from

nothing to nothing, is neutral.

There is no possibility that a person will go from nothing to eternal

misery, so it seems to me (but humility is appropriate) that this allows more

freedom for God. In a CI setting,

where the worst that can happen is nothing-to-nothing, avoiding eternal misery (for the unsaved)

is not a concern, and the focus can be on adjusting the "balance of

evidence" so it provides optimal benefits for believers who will spend

eternity in fellowship with God and other believers in heaven.

5. Extra-Biblical Influences on

our ideas about Immortality and Hell

Unfortunately, this part of the

paper seems necessary. It is an

interlude between Sections 1-4 and 6-7, which ask "what does the Bible

teach?" This question is

the main focus of my paper, because I

think Christian theology should be based on what the Bible teaches, as

described in 5.1. But

extra-biblical influences do occur so we’ll look at them, beginning (in 5.2)

with our Christian community, then moving into the effects of non-biblical

philosophies (in 5.3) before finishing (in 5.4) with a "recognize and

minimize" approach to coping with extra-biblical influences.

5.1 — Our Goal: Searching for Truth in the Bible

Bible-based theology should be our goal. During our search for truth, there is no

observable evidence about the characteristics and consequences of Hell, so as

evangelical Christians our main strategy for judging plausibility is to compare each theory with Scripture.

When we study the Bible, here are

some useful principles: • look at individual verses (including those in

Part 6 and elsewhere) in the context of essential overall principles;

• learn more about CI and EM (Part 2 is a good foundation, but learning

requires an investment of time and careful thinking) so you can evaluate each

idea based on accurate, thorough knowledge of what it actually is; • approach your evaluation with

open-minded humility, acknowledging that there is some Bible-based support for

each view.

I admit that the first principle (“learn more about CI and

EM”) is self-serving, because I think the more you learn, the more you’ll see

the strong biblical support for CI.

The apparent support for EM becomes much weaker after a careful

examination that includes an accurate understanding of CI and an open-minded

consideration of all available information. Therefore, I’m encouraging you to learn

more, and evaluate logically.

For example, Part 3 explains why

a correct understanding of CI removes the support for EM that apparently is

provided when Jesus describes the unpleasantness of hell. As explained in Section 3.1, suffering

in hell provides equal support for EM and CI. Therefore, any implication that

"anyone who believes what Jesus said about hell must believe EM"

is not justified, because everything Jesus said is compatible with

CI. On the other hand, some

things Jesus said — such as the burning of weeds in Matt 13:40, and

killing of rejecters in Luke 19:27 — do not seem compatible with EM.

There is agreement, among evangelical Christians who

advocate both EM and CI, that our theology should be based on the Bible. We just disagree about what the Bible

teaches. Why should there be

disagreement among intelligent people who love God and believe the Bible? First, “there is some Bible-based

support for each view.” Second, our

theology can be influenced by extra-biblical factors. Part 5 looks at the complex mixture

of biblical and extra-biblical influences in the community of Christians.

5.2 — Influences in the Christian Community

5.2a — The Inertia of Tradition

The inertia of tradition and psychology of conformity make

it easy to think like the majority, and difficult to think in other ways.

Try to imagine that very few people believe in Eternal

Misery, and you have just read a description of EM, plus a summary of the

arguments for and against it. Would

you believe EM? Would you discard

the orthodox belief — that after a period of fearful judgment and

suffering, nonbelievers are destroyed in hell and are thus forever excluded

from the Kingdom of God — and replace it with a doctrine of Eternal

Misery, proposing that God will keep nonbelievers alive so they can endure an

endless eternity of misery in hell? Would you be convinced that this new doctrine is more

compatible with your fundamental Bible-based beliefs, such as sin and the Fall,

and the goodness and grace of God as exemplified in the sacrificial

Substitutionary Atonement?

Unfortunately, tradition favors EM, and most evangelicals

— especially our leaders who feel a responsibility to teach orthodox

theology — assume (usually without much thought) that EM is clearly

taught in the Bible, even though (as explained in this paper) there are many

reasons to conclude that the Bible teaches CI rather than EM.

John Stott makes a plea for an open-minded consideration of

alternatives:

I have

great respect for longstanding tradition which claims to be a true

interpretation of Scripture, and do not lightly set it aside. The unity of the worldwide evangelical

constituency has always meant much to me.

But the issue is too important to suppress. I do not dogmatize about the

position to which I have come.

I hold it tentatively.

But I do plead for frank dialogue among evangelicals on the basis of

Scripture. I also believe that the

ultimate annihilation of the wicked should at least be accepted as a

legitimate, biblically founded alternative to their eternal conscious torment.[i]

I agree with Stott that CI (with annihilation of the wicked) should

be considered an acceptable alternative.

Frankly, I think it should be considered a better alternative, that it should be considered the biblically

supported view. For those who think

CI is clearly taught in the Bible, there are promising signs. In increasing numbers, evangelicals are

beginning to examine the scriptural basis for EM, instead of simply assuming it

is biblically justified. In 1989

the Evangelical Affirmations Conference refused to declare Conditional

Immortality unscriptural, even though they did make this declaration for

Universal Salvation. And in 1999,

Eternal Misery was not included in a summary of Gospel essentials, A Call to Evangelical Unity. I am encouraged by this, but for others

it may seem to be a cause for alarm, as discussed in the following section.

5.2b — Defending a Tradition

When defending an established set of religious doctrines, if

any part of the set is questioned there is a tendency to view this as a

challenge to other parts. This

perception is warranted IF (and only if) there are logical links between the

parts, if the doctrine that is being questioned forms a logical foundation for

other parts of the set, or is a logical outcome of other parts.

When evaluating CI, two principles are vitally important:

First, CI should be evaluated based

on an accurate understanding of what it really is. As explained in Part 2, CI differs from

EM only in the final state for the unsaved. In all other ways, CI and EM are

identical, so CI is compatible with all parts of a set of essential doctrines,

such as belief in the reality of sin, atonement, judgment, hell, miracles, and

(of course) the authority of the Bible.

In fact, the more carefully we study the Bible, the more strongly

supported is a conclusion that CI (not EM) is much more compatible with the

fundamentals of Christian faith, as explained in Parts 1 and 7.1. Therefore, we should reject any

implication that EM is a necessary part of Bible-based evangelical

theology. Instead of adopting a

debater's mentality in which "defending tradition" is the main focus,

a healthier goal is to study the Bible more carefully, to ask whether scripture

teaches EM or CI.

Second, we should avoid ad hominem arguments based on

"guilt by association."

This argument — implying that if we don't like some views of X,

and if X believes CI, then CI must be wrong — is not logical. Strangely, however, the argument is used

by some Christians who claim to base their beliefs only on the Bible, when they

imply that if anyone with unorthodox views (in other parts of their theology)

proposes CI, this is a reason to oppose CI.

It can be useful to think about extra-Biblical influences favoring

both CI and EM, and look at "who believes what," but only if

this is done by searching for logical connections between views, and

cause-effect interactions; some

ideas are in Appendix D4. But each

view should be evaluated based on everything it is, no more and no less.

5.2c — Improving People and Society

Two Criteria for Evaluation: Any theory, including a theological

doctrine about CI or EM, can be evaluated in terms of plausibility (how likely it is to be true) and utility (how useful it is for achieving desired goals). As explained in the first paragraph of

Section 5.1, “our main strategy for judging plausibility is to compare each

theory with Scripture.” This

section looks at utility.

To evaluate a theory based on its utility, first we define

goals. Then we ask, "How

effective is each theory (EM, CI,...) in helping us achieve these

goals?" For evangelical

Christians, three worthy goals are:

evangelism (helping others

gain salvation by becoming followers of Christ); discipleship

(helping Christians become better servants of Christ); societal stewardship (helping improve society).

Evangelism and Discipleship: These goals can be negatively affected

by a doctrine of Eternal Misery.

The hearts and minds of many people, both non-Christians and Christians,

are sickened by the thought of a God who would cause (or even just allow)

eternal torment in hell. These

people are less likely to turn their lives over to a God who would do this, and

to fulfill the greatest commandment by "loving God with all of their

heart, soul, and mind."

This lack of trust and respect (for a God who would cause or allow EM)

will hinder both salvation and discipleship. Although a threat of EM may encourage

some people to seek salvation, this ‘fire escape’ motivation is less likely to

promote the intimate spiritual relationship (of love, trust, and surrender to

God) that is the goal of Christian life.

With CI the motivation for conversion seems more pure, more likely to be

caused by true repentance and a sincere love for God. Yes, many advocates of EM do love and

serve God, but I think this is mainly a result of self-selection. Those who are highly motivated to be good Christians may think, due to

the weight of tradition, that devotion to God requires belief in EM. But I think these well-intending people,

at the deepest level of their being, are saddened by the dark shadow of EM, and

they would be able to more truly worship (with more inner honesty, at deeper

levels of intellect and emotion) a God with the character implied by CI instead

of EM.

Motivations for

Evangelism: Advocates of EM

often claim that without EM there will be less "felt need" for

evangelism, if there is no need to save the unsaved from endless torment in

hell. Although a decrease in

motivation is possible, I think our evangelism will be more effective —

due to the "hearts and minds" reasons described above — if we

are motivated by our desire to share the good news by telling others how they

can gain the very good things that are graciously offered by God, instead of

avoiding the bad things threatened by God.

Fear and Evangelism: With CI do Christians abandon a powerful

argument for religious conversion, when we tell a non-Christian that a failure

to accept Jesus as savior will cause them to burn forever in hell? If we are convinced that EM is true, of

course we should tell everyone about the horrors of EM-hell so they can avoid

it. But if EM seems to be false (for

the many reasons explained in this paper)

a reluctance to lose the persuasive "turn or burn" argument

should not be a factor in retaining EM.

If CI seems more probable, based on the Bible, we should use it for

evangelism. Colorful claims about

EM-hell will certainly make nonbelievers stop and think about how much they

want to avoid this infinitely horrible outcome, and what they are willing to do

so they can avoid it. But this

logic encourages a crass "fire escape" motivation for

conversion.* Instead, a decision to

accept the grace of God should be motivated by better reasons, by a true

repentance for sin, wanting a relationship with God, wanting to serve God and

fellow humans, working in cooperation with God's plan for your life, and (crass

yet positive) wanting to gain eternal life in paradise with God. * Of course, God knows all of

our thoughts, including our motivations, so a pseudo-repentance "conversion"

(if it’s only to escape the horrors of hell) will not result in salvation.

Justice and Evangelism: Another factor is the frequency and

vigor with which the justice of God is proclaimed. I think that in their hearts, many

Christians are secretly ashamed of EM, so they are less motivated to proudly

proclaim the judgment of God and the moral responsibility of humans. Peter Toon,

who is an advocate of EM, notes with sadness that “it is difficult to find

leading Protestant churchmen or theologians who actually believe in hell as

everlasting punishment [Toon should say ‘punishing’ not ‘punishment’] and who are prepared to state that belief in either sermons

or books.”[ii] By contrast, Christian can be

proud of CI-justice because although it is severe it seems fair. The death penalty of CI is the ultimate

fear of humans, the fear of losing our existence. But the overall change, from

nothing to nothing, is neutral and fair;

God gives life, and God takes away life. Contrast this with the fate of an

unsaved human in EM, who never asked to be born, yet ends up in hell with

eternal misery. Does this seem

fair? John Stott says,

“Emotionally, I find the concept [of EM] intolerable and do not understand how

people can live with it without either cauterizing their feelings or cracking

under the strain.” Stott then

continues, “But our emotions are a fluctuating guide to truth and must not be

exalted to the place of supreme authority in determining it. As a committed evangelical, my question

must be – and is – not what does my heart tell me, but what does

God's word say?” I

agree. This is the most important

question we can ask, so it is the focus throughout this paper.

Stewardship: A third goal is to help improve

society. When we think about this,

one simple approach is to view society as being shaped by the behaviors of

Christians and non-Christians. How

does EM affect the behavior of each group?

Christians believe they will avoid hell, so

EM probably has little effect, except perhaps (as discussed above) if EM is a

hindrance to the high-quality discipleship that encourages Christians to

"love God with their whole heart, soul, and mind" and "love

their neighbors as they love themselves" and thus help produce a better

society.

Do non-Christians believe EM? If a threat of future punishment is to

serve as an effective deterrent of bad behavior and motivator of good

behavior, the perceived probability

of the punishment may be more important than its severity. With EM,

"infinite punishing for finite sins" is terrifying (as described in Fear and Evangelism) but it seems

unfair so it seems less probable.

The nothing-to-nothing justice of CI seems more fair, more consistent

with the character of God that is revealed in the Old and New Testaments,

making CI seem more probable.

Therefore, CI might serve as a more effective deterrent to behaviors

that are immoral or criminal, and a motivator of good behaviors that are

beneficial for individuals and society.

More generally, I think a doctrine of CI would help to

promote better relationships between Christians and others, so we could more

effectively cooperate in a variety of ways that would help improve society for

all of us, as one aspect of loving our neighbors.

5.2d — Personal Influences (external and internal)

When we are thinking about theology, Christians are

vulnerable to the same types of psychological influences as non-Christians.

External Influences: Sociological pressures that encourage

conformity to the expectations of a group, which can influence us because we

have psychological desires to please other people and gain their approval, can

favor either EM or CI, depending on the group and the person who is potentially

being influenced. In most

evangelical churches, people (especially pastors and other leaders) will feel

pressures to believe and teach the "traditional view of hell" as

Eternal Misery. But outside

churches, a person can feel pressures to adopt CI due to its "kinder

and gentler" view of God.

Internal Influences: A desire for personal consistency that

will reduce unpleasant cognitive

dissonance can favor either CI or EM. CI is favored by a desire to reduce the dissonance

between two ideas: believing that

God is forgiving and merciful, and that God will cause eternal misery for many

people, including some of our friends and family. EM is favored when people gain more

confidence in their major decision with a high commitment demanded by Jesus

— “if anyone would come after me, he must take up his cross and follow

me, for whoever wants to save his life will lose it (Mark 8:34-35)” and “anyone

who does not carry his cross and follow me cannot be my disciple... [so before

deciding] first sit down and estimate the cost... [because] any of you who does

not give up everything he has cannot be my disciple (Luke 14:25-35) — by

believing that one of the many benefits of discipleship is avoiding the

immensely horrible fate of Eternal Misery. { comparing

benefits: Beliefs about "what

we get" are the same with EM or CI, but "what we avoid" is

larger with EM. }

5.3 — The Influence of

Extra-Biblical Philosophies

Soul-Immortality and Reincarnation

An intrinsic unconditional soul-immortality is not necessary in Christianity, because we have

the promise of a supernatural conditional body-resurrection

provided by God. But intrinsic

soul-immortality appears in many non-Christian worldviews, including Greek

philosophy, Hinduism, and spiritualism.

In theories of reincarnation developed by some ancient Greek

philosophers (Plato,...) there is a cycle of multiple human lives with

intervening periods in which the soul is purified in Hades where the soul can

see "the way things really are" more clearly, which helps the soul

prepare for its next human incarnation.

This repeating cycle (of birth, life, death, purification, birth,...)

continues until the soul is pure enough that it is no longer reincarnated.

Similarly, eastern religious philosophies (Hinduism,...)

propose an immortal soul plus reincarnation, with a spiritual goal of reducing

the desire for body-dependent experiences in the material realm; the ultimate goal is to eventually avoid

reincarnations by joining "the whole" in a state of disembodied

non-individual serene bliss.

In these concepts of reincarnation, embodiment is an

undesirable burden. By contrast,

Judaism and Christianity embrace the goodness and importance of life in the

body; we see sin, not the

material realm, as our major problem.

The spiritual goal of a Christian is for the whole person (including

mind and body) to live in sinless fellowship with God. We view death as an enemy to be overcome

(1 Cor 15:26,54) through the power and grace of

God, while other worldviews (Greek, Hindu, New Age, Spiritualist) see death as

a transition to another level of existence.

Unfortunately, Judeo-Christian

theology has been influenced by a concept of soul-immortality imported from

non-biblical philosophies.

Hades in the

Septuagint — An early influence on theology was the interaction

between languages that caused confusion when the Septuagint — a

translation of the Hebrew OT into Greek, beginning about 250 BC —

translated the Hebrew ‘sheol’ into the Greek ‘hades’. The intention was to

maintain the meaning of sheol

(the grave); but in Greek culture, Hades was more than a grave; in Greek philosophy, which included soul

immortality and dualistic mind-body distinctions, ‘Hades’ was a place of

suffering for conscious departed souls. This word, associated with philosophical

dualism, influenced the theology of some readers of the Septuagint but not

others. When readers who knew

Hebrew (and the meaning of ‘sheol’ in the Hebrew OT)

read ‘hades’

they thought "grave" and retained this original meaning. But readers who were influenced more by

Greek language and philosophy could read ‘hades’ and think "conscious

suffering".

The Timing of

Influence — Samuele Bacchiocchi

explains how this confusing interaction led to 2 schools of intertestamental

writing, Palestinian Judaism and Hellenistic Judaism, and why — because

NT writers understood and believed concepts from the Hebrew OT — “the

dualistic meaning of these important Greek words [Hades,...] is absent in the

New Testament. ... The New Testament view of human nature reflects the Hebrew

(Old Testament) and not the Greek way of thinking. ... The assimilation of

Greek dualism into the Christian tradition occurred after the New Testament was

written.”[iii] The NT writers had a holistic

Hebrew view of humans, but some later readers were influenced by

dualistic Greek philosophy, and this helped EM become the "traditional"

view of hell.

Influence in the

Church — How did the extra-biblical influence occur? First, throughout much of church

history, Greek philosophy was an important part of the dominant intellectual

culture in society, which included the church. Second, claims for immortality seem to

be rhetorically useful as a weapon against anti-supernaturalists,

because if a listener/reader can be persuaded that humans are immortal (which

many people want to believe anyway, for psychological reasons that are

described in Appendix C6) this shows that Christian claims for after-death

resurrections (of Jesus in the past, and all humans in the future) are not

unreasonable. But I think it’s

better to simply say "the Bible tells us that God has supernatural

power so He can do things we don’t understand" and avoid claiming things

(like an intrinsically immortal soul) that are not claimed in the

Bible.

5.4 — Coping With Extra-Biblical Influences

Recognize and

Minimize: The previous two

sections (about the Christian Community and non-Biblical Philosophies)

describe non-Biblical influences that can affect our interpretations of what

the Bible teaches about the Final State.

I think we should recognize that theology can be

influenced by extra-biblical factors;

then, in our effort to make our search for Bible-based theology more

effective in finding the truth, we should try to minimize the biasing

influence of these factors.

We should want our theology to based on what the Bible teaches,

carefully analyzed with thinking that is logical and unbiased, using generally

accepted principles for interpreting the Bible. We should pursue this noble goal by

using it as an aiming point and taking actions that will move us closer to

it, while humbly recognizing that we haven't yet achieved it and never will.

Bias and Falsity: Even if a person (or group) is motivated

to be biased, this does not mean their evaluation process will be biased, or

their conclusion will be wrong.

Why? Because with discipline

they can overcome their tendency toward bias; or maybe the evidence really does point

to the desired conclusion, and "the way they hope the world is"

corresponds to "the way the world really is," so their bias does not

lead to a wrong conclusion. But

even though a biased conclusion is not necessarily false, if we want to find

truth our "best way to bet" is to base our conclusions only on

evidence-and-logic, in a process of unbiased evaluation. Because our goal is Bible-based

theology, we should try to minimize all extra-Biblical influences.

6. Four Bible Passages often claimed as support for Eternal Misery

As evangelical Christians, we should evaluate every

theological doctrine by asking "what does the Bible teach?" Four passages claimed as biblical

support for Eternal Misery are: Matthew 25:31-46, Luke 16:19-31, Revelation

14:9-11, Revelation 20:10.

This section examines these passages to show that they do not support

EM. For other passages about

EM-vs-CI, see Section 7.6. a useful

principle: In addition to carefully

examining individual passages, we should broaden our perspective by also

looking at the "big picture" of major themes in the Bible, as in Part

1.

6.1 — Matthew 25:31-46

In the final judgment, Jesus will say to some, “depart from

me, you who are cursed, into the eternal

fire prepared for the devil and his angels ... [and] they will go away

to eternal punishment, but the

righteous to eternal life. (Matthew

25:41,46)”

Section 3.2 explains why “eternal punishment” does not

support a conclusion of EM in hell, unless: A) we think everlasting punishment (a result) requires everlasting

punishing (a process) by treating aionios as if it

was a verb instead of the noun that it is, or B) if we assume that every

resurrected human will be immortal.

Eternal fire and eternal worms are discussed in Section

7.1e.

6.2 — Luke 16:19-31

In this parable of Jesus, we hear about a rich man (who

during his life on earth showed no compassion for Lazarus the beggar) “in hell,

where he was in torment,... in agony in this fire.” All of the characters have

bodies; the rich man and Abraham

have tongues (they can speak and hear) and eyes (they can see each other), and

Lazarus has fingers.

Maybe this passage should not be included here. Why not? The “torment” and “agony” are

consistent with either CI or EM because both views propose suffering in hell; their only difference is the

duration of suffering — is it temporary as in CI, or permanent as in EM

— but the duration is never described in Luke 16:19-31.

When we interpret this passage and the "life after

death" it seems to describe, instead of thinking about a vague generic "afterlife"

we should think logically, with precision.

We should ask "what stage in the afterlife (if any) is being

described?" and we should consider the fact that, as stated in Part 2 and

discussed in Appendix B, Christians have two common views about the intermediate state between our

individual deaths and the universal Resurrection of all humans: we will sleep, or we will be a conscious

soul without a body. Christians who study the Bible carefully

rarely propose life with a body

during the intermediate state, because the Bible so clearly teaches (in many

places) that we receive bodies at The Resurrection, not before then.

A Parable of

Life-after-Death?

In Luke 16:19-31, are the characters (Lazarus, the rich man, and

Abraham) conscious souls in the intermediate

state? If so, there is logical

inconsistency because these "souls without bodies" have bodies (with

eyes and ears, fingers and tongues) before The Resurrection when God gives

bodies to the dead! But it also

cannot be the Final State, after The

Resurrection, because the rich man’s brothers are still alive.

This story does not accurately describe any commonly

proposed state of existence after death, in either the intermediate state or

final state. Therefore, it probably

was never intended to provide details about post-death

life except to state that it will be unpleasant for the wicked. Instead, its main purposes were to teach

a valuable lesson about how to live in our pre-death

life, and to predict (regarding his own death and resurrection) that if

people really want to not-believe they “will not be convinced even if someone

rises from the dead.”

If we ignore the details of the story, and just say

"Jesus tells us that people who don't behave with compassion now will