This diagram shows how we use 3 Elements (Predictions & Observations, Goals) in 3 Comparisons to ask Two Kinds of Questions:

This diagram shows how we use 3 Elements (Predictions & Observations, Goals) in 3 Comparisons to ask Two Kinds of Questions:

This page looks at...

• REALITY 101 — Essential Concepts (rational and idiotic)

• and More about Postmodernism

• Do scientists create reality? — This is one kind of postmodern idiocy, in the foolish ideas – claiming that scientists “create reality” – proposed by a few scholars, but opposed by most scholars.

plus The Limits of Logic and "What makes relativism radical?"

In the title – Reality 101 – the "101" is appropriate because this page...

• will examine only basic concepts of reality, focusing on ideas that are simple and logical, that should not be controversial. {it's 101, not 909}

• will ask only the easy questions, those that can be logically understood using the “minds” part of our “hearts and minds.” The difficult questions also involve our hearts, and our values.

Rationality and Idiocy: This page describes the rationality of humble postmodernism, and also the idiocy that occurs when a good idea — it's a claim that we should recognize the limits of logic — becomes a bad idea when it's taken to foolish extremes without sufficient balance from rational critical thinking. {one example of idiocy is when radical postmodernists claim that “scientists create reality”}

What is truth? With the correspondence definition of truth that we always should use, truth is what actually is happening in reality (in the present) or (in the past) what actually did happen in reality.

A humanly constructed theory claims to describe reality. When we make claims based on a theory (by assuming the theory is true, and using “if... then...” logic by thinking “if this theory is true, then ___”) we are making truth-claims about the reality of what is happening now, or did happen in the past. Our truth-claims are true if they are correct, if they correspond to the truth of what actually is happening (or did happen) in reality; and our truth-claims are false if they are incorrect, if they do not match the truth defined by reality.

other terms: The important meaning for “theory” (or theory-based “truth claim”) should never be distorted by calling it “truth”. { with varying degrees of rationality, it can be labeled with many terms: a belief, hypothesis, conjecture, speculation,

opinion, premise, assumption, conclusion, certainty, fact,... }

paradigm, principle,

To illustrate the essential difference between truth and truth-claims, think about this famous example: Between 1500 (when almost everyone believed that the sun & planets revolved around the earth) and 1700 (when almost every educated person believed that the earth & planets revolved around the sun), what changed and what did not change?

Did the reality change? Did the reality (the motions of planets) change from earth-centered (in 1500) to sun-centered (in 1700)? No.

Did the truth change? No. Because truth is determined by reality, what was true in 1500 (the earth and planets really moved around the sun) was also true in 1700.

Did our truth-claims change? Yes. Our humanly constructed truth-claims about the motions were different in 1500 and 1700. Thus, there were changes in the realities of humanly-constructed science, philosophy, religion, and culture, as explained below.

We should distinguish between two kinds of external reality and internal belief :

is constructed by humans |

not constructed by humans |

|

occurs internally |

humanly-constructed belief |

this combination is impossible |

occurs externally |

humanly-constructed reality |

human-independent reality |

A modern example of a humanly-constructed reality occurs when we actualize the humanly-constructed belief — the societal agreement, adopted by consensus and institutionalized in traffic laws — that “life will be better” if all drivers agree to stop for a red light and go for a green light, and that in America or continental Europe (but not in Britain or Japan) we will drive on the right side of the road.

But if there is a collision, caused by someone running a red light or driving on the wrong side or making some other mistake or by a mechanical error, humans do not construct the laws of physics that determine what happens during the collision. Yes, we can minimize the harmful results of a collision by constructing cars with air bags, collapsible bumpers, and other safety features. But we achieve this humanly-constructed reality (in which we have safer cars) by acknowledging and understanding a human-independent reality (for the physics of collisions). We can build safer cars by cooperating with reality, by designing cars within the context of the physics that really exists, by deciding to adjust our humanly-constructed beliefs (that guide our thinking while we're designing cars) to match the human-independent realities of collision-physics. But we cannot build safer cars by denying this reality, by trying to overcome reality through faith in a kinder-and-gentler physics that we could foolishly construct and believe. During a collison we would prefer this physics, but we cannot produce it, instead our thoughts-and-decisions-and-actions should occur within the context of the actual human-independent reality.

If we recognize the existence of two kinds of reality — human-independent and humanly-constructed — our worldview is less simple than if we ignore this distinction and lump everything together into one category. But a view that “splits” instead of “lumping” will see things (and describe things) in a way that is more accurate, and will avoid the confusions that occur when we try to think about both types of reality in the same way.

Our thinking and communicating should be different for the two types of reality. Some ideas about “beliefs creating reality” are rational for humanly-constructed realities (for example, making truth-claims about the solar system, or deciding whether to drive through a traffic-lighted intersection or to stop) but these ideas are ludicrous for human-independent realities (such as the actual motions in our solar system, or the actual laws of collision-physics) in which external reality is not affected by human beliefs or social agreements.

This important distinction also will help us understand correct causal relationships. Yes, our thoughts will cause consequences when “what we think” is converted into “what we do,” when our human thoughts cause our human decisions-and-actions. But for human-independent reality, our believing that something is true cannot (and does not) cause it to be true. / We can believe that an independent reality is true because it appears to be true (because the consequences of its existence-and-operation produce evidence that persuades us of its existence-and-operation) but the correct sequence of causation is “reality → evidence → belief” instead of “belief → reality”.

note: Some highly speculative interpretations of quantum physics claim that human observation (or human consciousness) can directly affect reality. But in a page about quantum physics and reality I use principles of quantum physics to explain why these “mystical physics” claims are not supported by science and why, at the quantum level and everyday level, human thoughts-and-decisions-and-actions can affect some aspects of reality but not other aspects; we can affect humanly-constructed realities, but we cannot affect human-independent realities.

This distinction also is helpful when we ask, “Are scientific theories constructed or discovered?”

Contemporary scholars claim that scientific theories are humanly constructed, and this is true. But only in some ways. Yes, between 1500 and 1700 our theories (or truth-claims, our beliefs) about the solar system were constructed and they did change. But our theories improved because we discovered more about the independent reality (the human-independent reality) that was not constructed by us. In order to construct accurate theories about a human-independent reality (like the solar system) our theory construction must be constrained and guided by what we know about this external independent reality, due to what we have discovered about the reality.

By contrast, if sociologists are constructing theories about a society (which is a humanly-constructed reality), there will be interactions between theories they are constructing and the reality they are describing. These interactions will — if the sociologists and their theories are known by people in a society, and are influential in this society — let the scientists help “construct the reality” of the society. But they can do this only because human society is a humanly-constructed reality, not a human-independent reality.

Summary: It's important to make a clear distinction between human-independent reality and the humanly-constructed reality that is constructed (is produced or is changed) when humanly-constructed beliefs are converted into human decisions-and-actions. Confusion will occur if there is an erroneous failure (or stubborn refusal) to distinguish between these two kinds of reality. Therefore, if we want our thinking to be more precisely-accurate and less confused, we always will ask “Which type of reality is it?”

In the traditional correspondence definition of truth, truth is determined by reality, and a truth-claim is true (it's correct) if it corresponds to the actual state of reality, either now or (for a truth-claim about history) in the past, if it matches the way the world is or was.

But in the non-correspondence definitions of truth used by postmodern relativists, “truth” is determined by human decisions based on human criteria, not by reality. In a consensus definition of truth, a truth-claim is considered to be true within a community if the claim is accepted by most people in this community. In a coherence definition of truth, the truth of a truth-claim depends on its relationships with other statements, on how coherently it fits into a system of statements that are considered (by those constructing the system) to be true; in scientific reasoning, a theory is considered “probably true” when it is supported by evidence-and-logic during a process of logical evaluation that includes internal coherence plus other criteria. With a pragmatic definition of truth, a statement is true if it produces satisfactory results when it is used as a basis for decisions-and-actions.

Instead of viewing these non-correspondence terms as “definitions of truth” it's more useful to view them as “characteristics of plausible knowledge,” as criteria for evaluating claims-about-truth, because a claim becomes more plausible – i.e. we think it seems more likely to be correct – if the claim has consensus (among experts), is coherent (logically), and is pragmatic (because “living the claim” produces useful results). These "criteria for evalutating" are useful – along with basic Scientific Logic – in our {more about “absolute truth”} pursuit of plausible knowledge.

To avoid confusion, I think the word "truth" should be reserved for a correspondence definition; rational people should NEVER use the word "truth" in any other way, and when other people do this we should challenge them, gently and logically. The non-correspondence definitions of truth — by consensus (claiming that truth is a theory accepted by a majority), coherence (truth is a logically-justifiable belief), pragmatism (truth is a useful principle), or in other ways — are humanly constructed claims about what is true, so they should be called truth-claims (or theories, beliefs, principles,...) instead of truth.

The incorrect use of "truth" is seen in the first two paragraphs of Wikipedia's page about truth: First, "Truth is the property of being in accord with fact or reality." Yes, this is correct. Second, "In everyday language, truth is typically ascribed to things that aim to represent reality or otherwise correspond to it, such as beliefs, propositions, and declarative sentences." This also is correct, as a description of the unfortunate fact that sometimes "in everyday language" the word truth is used in these incorrect ways, to describe truth-claims that "aim to represent reality" but are not the reality that determines truth; "beliefs, propositions, and declarative sentences" are claims-about-truth, but are not truth.

Here are two terms that I think should not be used:

my truth — A common mis-use of "truth" is a pet peeve of mine, because it's so foolish yet so popular. Unfortunately often, someone tries to defend their own truth-claim by saying “I'm speaking my truth, and you are speaking your truth.” This mis-use of the word "truth" is illogically foolish and falsely misleading, because what they actually mean (so it's what they should say) is “I'm speaking my belief” or “I'm speaking my ” where the blank can be filled with belief, truth-claim, opinion, theory, or principle. But they certainly should not claim to be “speaking a truth” or “speaking the truth.”

absolute truth — I'm disappointed when a fellow non-relativist makes claims about absolute truth. This term is confusing because absolute truth has many possible meanings. • If the intention is to make a truth-claim – especially about an independent reality (not a humanly constructed reality) – by using a correspondence definition of truth, then absolute truth = truth, so adding "absolute" isn't necessary and isn't helpful. Instead, just clarify the intended meaning by calling it a truth-claim and explaining that the intended meaning of "truth" is correspondence-based truth, which is reality-determined truth. Or say “absolute truth” and explain why this is a contrast with “relative truth” that actually isn't “truth” in any logically-meaningful way. • If the intended meaning of absolute truth is to describe a fact that is always true (in all cultures & situations, in the past, present and future), this universally-true fact can be called a universal fact (or universal truth) or general fact (or general truth) instead of absolute truth, to clarify the intended meaning. {more about “absolute truth”}

In science – as in most other areas of life (*) – proof is impossible, but scientists can develop a rationally justified confidence in the truth or falsity of a theory.

Why is proof impossible, and how can scientists develop confidence? This is discussed in The Limits of Logic, which explains why modern science has given up the quest for certainty, and has decided to aim for a high degree of plausibility, for a rational way to determine "what is a good way to bet." Basically, a rationally justifiable confidence can occur when a person has strong evidence and uses correct logic, in their evidence-based logical evaluation of their truth-claim. {* In some areas of life, proof is possible. For example, in mathematics we can prove that “2 + 3 = 5” if we define each of the five concepts ( 2 , + , 3 , = , 5 ) as in our usual system of math. But in science – and for the most important questions in life – proof is impossible, so 100% certainty is impossible. }

In most situations the perspective of most scientists is a critical realism that combines realist goals (wanting to find the truth) with critical evaluation (willing to be skeptical about the truth-claims associated with a particular theory, to estimate its degree of rationally justified confidence).

Our degree of confidence in a theory can be summarized in its theory status, which is an estimate of a theory's plausibility. But a scientist's estimate of a theory's utility can supplement their estimates of its plausibility when they are evaluating the status of a theory — and therefore this theory's contribution to our overall system of rationally-justifiable knowledge — by using evaluation criteria that can include a theory's pragmatic utility & coherence plus consensus in addition to using logical Reality Checks. The concept of theory status is useful because it allows flexibility in our thinking. If the status of a theory is extremely high or low, we can choose to accept or reject this theory. But we have options because, in addition to this binary yes-or-no choice to either accept-or-reject, we also can think in terms of a status (a degree of confidence) that can vary along a continuum ranging from high to low, from yes to no, with varying degrees of confidence between these extremes. Although we cannot have certainty – because there will be no “proof” of what's true – by using evidence-and-logic we can find “good ways to bet.” An important part of a truth-claim is the confidence assigned to it by the claimer; there is a difference between claiming “maybe this is true” and “I'm certain this is true.” This is why I emphasize the utility of this concept:

We should try to have logically appropriate confidence (i.e. logically appropriate humility) in our personal thinking {internally} and {externally} our interpersonal claiming. When we think about theory status (i.e. we think about degrees of confidence) it will be easier to view theories with a logically appropriate humility because we can avoid the extremes of a silly radical relativism (which insists that if we cannot claim certainty, we can claim nothing) and the over-reaction that produces arrogantly overconfident claims (in thinking that if we want to avoid the extreme of not claiming any confidence, we must claim the total confidence of certainty). An appropriate humility recognizes that, based on evidence-and-logic, in some situations only a low level of confidence is justifiable, while in other situations an extremely high degree of confidence (which is almost a certainty) is justified. / Bertrand Russell said "error is not only the absolute error of believing what is false, but also the quantitative error of believing more or less strongly than is warranted by the degree of credibility properly attaching to the proposition believed, in relation to the believer's knowledge." If we are "logically appropriate" in our confidence (our humility), this will help us avoid 2 of these 3 kinds of error.

an example: In 1600, based on the best available evidence and logic, a sun-centered theory deserved an intermediate status, and it received a mixed reception. Some scholars argued for it, others were against it, and everyone was able to support their view with some evidence, logic, and philosophy. During a 200-year period, from 1500 to 1700, the human consensus changed from almost-certainty (but with a mismatch between confidence and truth, due to widespread belief in a theory that was wrong) to intermediate levels of confidence — that gradually, due to new evidence & improved analysis, and changes in those who were considered to be the “authorities” influencing societal evaluations of truth-claims, shifted in favor of a sun-centered theory — back to almost-certainty (with belief in a theory that we now claim, with a high degree of confidence that approaches certainty, actually is true). But during these changes in humanly constructed theories about truth, the actual truth — which was determined by human-independent reality, by the actual motions of the earth, planets, and sun — remained what it was, unchanged by human debates.

appropriate humility is not maximum humility: Sometimes the evidence for a truth-claim is so strong that, for practical purposes, it seems rational to adopt a feeling of certainty about the truth of this claim, to consider it “proved beyond a reasonable doubt.” For example, some claims made by science — that the earth is roughly spherical, rotates, and orbits the sun once a year, or that heavier-than-air objects will fall through air toward the earth — seem so well established that it's difficult, and it might be unwise, to avoid thinking of them as "facts" about which we can be certain. For these claims, it seems appropriate to say “there is very little rational justification for humility.”

Although a claim of “certainty” cannot be justified by rigorous logic, I think that — despite the protests of skeptics — we can have a high degree of rationally justified confidence in most of the truth-claims made by modern science. {details: The Limits of Logic, Radical Relativism} {the foolishness of claiming “scientists create reality”}

A reason for caution is the recognition that some theories we once thought were correct (re: planetary motions and other phenomena) are now considered wrong. Similarly, some of our current theories also could be wrong. But I think most are correct, or at least approximately correct.

Later this page asks "Do scientists create reality?" and we've been looking at relationships between confidence and truth, including these: when strong confidence seems justified, this confidence will not affect a human-independent reality; and when a general humility seems justified and we are not highly confident about any current theory, truth does exist even though we don't know (with certainty) what is true.

When there is a discussion about truth, ask yourself:

Are we thinking about the truth (which is determined by reality) or a truth-claim (which is a human theory about reality)?

Is the reality analogous to movements in the solar system (human-independent reality) or is it like driving on a specified side of the road (humanly constructed reality)? These two types of reality have different characteristics, and claims that are rational for one type can be silly for the other type.

For either type of reality, the certainty of logically rigorous proof is impossible, but logically justifiable confidence is possible.

For human-independent reality, a high level of confidence in a theory cannot make it true. But even though we cannot control the independent reality of our solar system, we (individually and in groups) do “construct our personal views-of-reality” (by constructing our worldviews) and we partially “construct our realities” when our decisions partially determine our life-situations. { I say "partially" because some aspects of our situations are beyond our control. } / But even though the truth of a theory is not affected by our confidence that the theory is true (or is false), if our confidence seems justifiable – if it's based on a solid foundation of evidence and logic – this may be an indication that the theory is true (or is false) so it's “a good way to bet.”

In the title, "pursuing truth" means trying to determine what is probably true so it's “a good way to bet.” This kind of action – by “searching for truth” – is possible. It's a realistic goal. By contrast, it's unreasonable to make claims that we can achieve a goal of knowing what is certainly true, so we “know truth” after “finding truth” and then knowing-with-certainty that we have found truth.

And "everyday science" means using the basic logic-of-science for everyday living. During daily living, all of us learn from experience by “doing experiments” – with our actions & thinking, or just being aware of what's happening – because (with a broad definition) an Experiment is any situation that produces Experience, that provides an opportunity to get Experimental Information with Predictions or Observations. How? You produce Experimental Information when you make Predictions (by imagining in a Mental Experiment) or make Observations (during the actualizing in a Physical Experiment). Every Prediction-Situation or Observation-Situation is an Experiment, so Experiments include many things you do, and most things you experience. Your total experiences include your first-hand experiences with events you personally Observe (that you remember in your Personal Memory, from your own experience in the distant past or recent past) plus the second-hand experiences (found in our Collective Memory) that were Observed by someone else, then later (in a report or recording) you hear it and/or see it, or (in a web-page, book,...) you read about it.

note - The home page of my website about Education for Problem Solving includes a section about Science Process – it's the 3rd of 4 Stages – that is quoted (with minor changes) below.

People use two kinds of design, trying to achieve two different objectives: during General Design we're trying to design (to find, invent, or improve) a better product, activity, relationship, and/or strategy; during Science-Design we're trying to design a better explanatory theory, so we can understand the what-and-how of reality more accurately and completely.

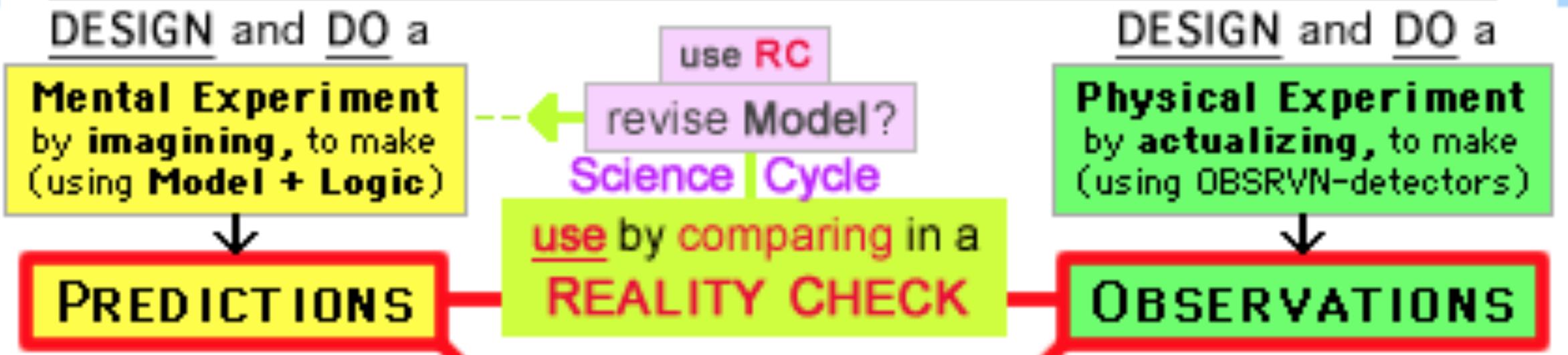

This diagram shows how we use 3 Elements (Predictions & Observations, Goals) in 3 Comparisons to ask Two Kinds of Questions:

This diagram shows how we use 3 Elements (Predictions & Observations, Goals) in 3 Comparisons to ask Two Kinds of Questions:

• The Design Question (used in two Quality Checks during General Design) asks “how close is the match?” when your Goals (for a satisfactory Problem-Solution) are compared with Predictions or Observations — so you're asking “how well would This Option achieve My Goals?” or “how high is its Quality?” with Quality defined by Goals — and...

• The Science Question (used in a Reality Check during Science-Design) asks “am I surprised?” and answers “yes” if there is a mis-match when Predictions & Observations are compared.

doing a Reality Check: Science-Design (commonly called science) uses logical Reality Checks to construct a theory-based Explanatory Model – that describes “how the world works” in a particular Experimental Situation – with a goal of explaining the reality of what is happening, how, and why. As shown in this action-diagram, during a Reality Check you compare Predictions (made in a Mental Experiment by "using Model + logic" to imagine what will happen in the Experimental Situation, or by remembering-and-assuming)* with Observations (made in a Physical Experiment by actualizing the Experimental Situation and "using Observation Detectors") to see how closely they match. In other words, you logically apply an Explanatory Model (for “how you think the world works” in this Experiment) to make Predictions (about “how the world will work”) that you compare with Observations (of “how the world really works”) to check the accuracy of Predictions based on this Model. By doing this, you're using Experimental Information (Predictions & Observations) to get knowledge about your theory-based Model for “how the world works” so your understanding of the world can become more accurate-and-complete.

doing a Reality Check: Science-Design (commonly called science) uses logical Reality Checks to construct a theory-based Explanatory Model – that describes “how the world works” in a particular Experimental Situation – with a goal of explaining the reality of what is happening, how, and why. As shown in this action-diagram, during a Reality Check you compare Predictions (made in a Mental Experiment by "using Model + logic" to imagine what will happen in the Experimental Situation, or by remembering-and-assuming)* with Observations (made in a Physical Experiment by actualizing the Experimental Situation and "using Observation Detectors") to see how closely they match. In other words, you logically apply an Explanatory Model (for “how you think the world works” in this Experiment) to make Predictions (about “how the world will work”) that you compare with Observations (of “how the world really works”) to check the accuracy of Predictions based on this Model. By doing this, you're using Experimental Information (Predictions & Observations) to get knowledge about your theory-based Model for “how the world works” so your understanding of the world can become more accurate-and-complete.

using a Reality Check: If you ask The Science Question and respond “yes, I am surprised” you can revise the old Model to make a new Model. Why? So you can produce a better match between your Model-based Predictions and Reality-based Observations. How? {The section continues with a description of how we revise an existing Model to make a better Model.}

* two ways to Predict: You can make a Prediction in two main ways,... 1) by simply remembering a similar Experimental Situation in the past, and assuming “what happened before will happen again” or 2) by constructing an Explanatory Model (typically it's a Mental Model) for the Experimental Situation, and using IF-then logic, by thinking “IF my Model is correct, then will happen,” and the filled-in blank is your Prediction.

MORE about PostmodernismHopefully, the logical foundation in Reality 101 will help us avoid much of the silly dialogue (with each side misunderstanding the other) that occurs between proponents and opponents of postmodernism. But questions remain, and some of these are examined in the following sub-sections. Much of what you see below is personal commentary. It contains ideas that I hope will stimulate your thinking, and is not intended to provide an in-depth comprehensive analysis of the complex issues being examined. But I think you'll find it interesting and useful.

Postmodernism and LanguagePostmodernists emphasize the importance of language, which affects how we think and how we interact with each other. Yes, language is important in our thinking, communicating, and constructing of theories. Postmodernists are skillfully using language to support their views and increase their influence. Non-postmodernists should pay more attention to the uses of language in society.

Where is the proof?This is a question we should avoid. Instead we should ask "Where is the evidence?" because when someone asks "Where is the proof?" they are implying that the evaluation standard should be the 100% certainty of proof, instead of a high level of rationally justifiable confidence based on a logical evaluation of evidence. Unfortunately, the use of an unreasonably high standard (if we demand proof) tends to reinforce the skepticism of relativism and postmodernism.

Modern and PostmodernCurrently, postmodernism supplements modernism, but has not replaced it. Both perspectives exert strong influence. To some extent, the type of reality affects the type of influence. Modernism, which emphasizes the authority of science, is more influential for questions about independent realities. Postmodernists critically analyze the process by which humanly-constructed realities (such as scientific theories) are constructed, and if they conclude that a process-of-science is flawed they may challenge the credibility and authority of scientists.

Pluralism is not Relativismpluralism is not the same as relativism: The existence of many views (pluralism) does not indicate that all of these views are equally credible (as claimed in extreme relativism), any more than the existence of many answers on a multiple-choice exam indicates that we can have no basis for thinking that any of the answers is more plausible than the other answers.

A Postmodern View of Truth (Do we create truth?)Some perspectives on truth blur the line between belief and reality. For example, Stanley Grenz (in A Primer on Postmodernism) says, "Postmodernism affirms that whatever we accept as truth and even the way we envision truth are dependent on the community in which we participate. ... There is no absolute truth; rather, truth is relative to the community in which we participate." {Although Grenz is reporting on postmodernism “from the outside” and (like me) is not a proponent, I think he accurately summarizes postmodernist views.} The first sentence correctly acknowledges the fact that human beliefs are constructed by humans. But the second sentence confuses these beliefs with reality. It would be correct to say "beliefs about truth are relative to the community..." but he says "truth is relative to the community" thereby equating truth with belief, with "whatever we accept as truth." This definition of truth is a serious error because confidence in a truth-claim cannot make the claim true, although the confidence may indicate “a good way to bet.” { As emphasized in Part 1, to avoid confusion we must distinguish between human-independent reality and humanly constructed reality. } Is relativism illogical and self-refuting?Some of its critics make this claim, but I disagree. To see why, let's look at two assertions that could be made by a relativist: 1) A statement that "all theories are false" IS inconsistent and incorrect, because the statement is itself a theory, so if the statement is true, then at least one theory is true, and the statement is false. 2) A statement that "all theories are uncertain" IS NOT internally inconsistent because when you say "if you are correct, then your own theory is uncertain and you can't be certain about its truth" the claimer will agree that "yes, this is what I said." #1 is logically self-refuting, but this isn't the claim usually being made by relativists. Instead they claim #2 (which is not logically self-refuting) by saying “we can never be certain about anything” or, with more humility, "I'm not certain that we can ever be certain about anything." In fact, I agree with #2 because "proof is impossible." But the difficulty with postmodernism is that "if a good idea is taken to extremes... there may be undesirable consequences," as explained later. Yes, "proof is impossible" but rationally justified confidence is possible, and sometimes "a high degree of confidence (which is almost a certainty) is justified." Unfortunately, some people claim that "relativism is self-refuting" in a well-intended but futile attempt to find a simple flaw in postmodern relativism. I think serious flaws do exist, but usually self-refutation is not one of its flaws. On the other hand, a claim that "it's wrong to say someone is wrong" is logically inconsistent, as discussed later when we compare Tolerances (New and Conventional) by asking whether it's wrong to say "I think you're wrong."

Is it rational to reject relativism?As explained earlier, a major claim of moderate relativism — about the impossibility of proof, in many situations — is justifiable, and most non-relativists agree. And we cannot challenge postmodern relativism by arguing that it logically refutes itself. Therefore, should we accept it? No, because there are other reasons for rejecting relativism in its more extreme forms. We should not move from reasonable moderate relativism to unreasonable radical relativism. We should avoid the undesirable consequences that occur when — if someone declares that "if you cannot claim certainty, you can claim nothing" — a good idea is taken to extremes. For the important questions in life, most rational people will agree that even though the certainty of logically rigorous proof is impossible, we can (and should) aim for a rationally justified confidence. A reasonable amount of relativism is logical and wise, but "too much" is foolish. Postmodern Tolerance and Conventional ToleranceIs it wrong to say "I think you're wrong"? A claim that "it's wrong to say that someone is wrong" seems intolerant, even though it's often made "in the name of tolerance." In addition, it may be self-refuting (logically? morally?) because the claimer is doing something — saying "it's wrong to..." — that he has declared to be wrong. Saying "it's wrong to say someone is wrong" is logically inconsistent, and is hypocritical. Claiming "it's wrong to say ‘I think you're wrong’" is even worse because it expands the range of what is not being allowed. But modified versions of this claim — "I think it's wrong to say someone is wrong" (or "I think it's wrong to say ‘I think you're wrong’"?) — are more tolerant (in its conventional meaning) and less restrictive, with less obvious intent to censor. Let's compare two views of tolerance, postmodern and conventional. In a strange twist of language, a postmodern new tolerance can produce intolerant censorship. This occurs when the postmodern tolerance — which claims that tolerating other views (and choices, actions,...) requires an absence of evaluative criticism — prevents some views from being expressed and considered. By contrast, conventional tolerance — which encourages open communication, a respectful acknowledgment of disagreements, a mutual commitment to courteous thoughtfulness, and listening with an intention to understand — promotes attitudes and actions that usually are beneficial for individuals and for society. |

Do scientists create reality?

Do scientists study nature, or create nature? Somewhat amazingly,

Woolgar (1989) argues that scientists construct objects through their representations of them. Objects, according to Woolgar, whether they are countries or electrons, are socially constructed entities, and do not exist aside from this social construction. Science is therefore not the process of finding things that already exist, but the process of creating things that were not there to begin with. (Finkel, 1993, p 32, with my emphasis)

This amazingly silly idea survived for at least 10 years in the mind of Woolgar, because a decade earlier Latour & Woolgar (1979, p. 64) claimed that "the bioassay is not merely a means of obtaining some independently given entity; the bioassay constitutes the construction of the substance." This bizarre super-radical constructivism (*) — which also is illustrated when Wheatley (1991, p. 10) declares that "objects do not lie around ready made in the world but are mental constructs" — is criticized by Matthews (1994, p. 152) who explains a crucial distinction: "Where he [Wheatley] goes wrong is in failing to distinguish the theoretical objects of science, which do not lie around, from the real objects of science, which do lie around and fall on people's heads."

* These super-radical claims are an unjustifiable extrapolation of basic constructivist views of learning that are highly respected (are accepted by most psychologists & educators, including me) so the "amazingly silly" claims – that “scientists are constructing reality” – should not be called constructivism, instead we should use a different term.

A description of the way scientists actually think about the observation of real objects — no, it is not necessary to “create the reality” of the objects that are being studied — is provided by a real scientist, a cell biologist:

First, I assume that cells are real objects. Second, I assume that other people can see and think about things the way that I do. ... Others' basic experience of reality is similar to mine. If they were standing where I am standing, they would see something very similar to what I see. ... Scientists act as if... the observations made by one scientist could have been made by anyone and everyone. (Grinnell, 1992, p. 20; emphasis in original)

A prominent philosopher gives another excellent description of truth and its relationship with reality:

Whether a statement is true is an entirely different question from whether you or anybody believes it. ... There can be truths that no one believes. Symmetrically, there can be beliefs that are not true. ... The expression “it's true for me” can be dangerously misleading. Sometimes saying this... means that you believe it. If that's what you want to say, just use the word "belief" and leave truth out of it. However, there is a more radical idea that might be involved here. Someone might use the expression “true for me” to express the idea that each of us makes our own reality and that our beliefs constitute that reality. I will assume that this is a mistake. My concept of truth assumes a fundamental division between the way things really are and the way they seem to be to this or that individual mind. (Sober, 1991, pp. 15-16)

Next, Sober illustrates what he considers to be a valid meaning for "thoughts becoming reality" by describing how a person's thoughts (if he thinks that he won't hit a baseball) can affect his actions (by making him swing the bat too high, so he doesn't hit the baseball). By contrast,

What I do deny is that the mere act of thinking, unconnected with action or some other causal pathway, can make statements true. I'm rejecting the idea that the world is arranged so that it spontaneously conforms to the ideas we may happen to entertain. (Sober, 1991, p. 16)

These quotations, from Grinnell and Sober, a scientist and a philosopher, summarize the most important concepts of Reality 101 — in the distinction between humanly-constructed realities (our beliefs, scientific theories, baseball actions, plus cultures & values,...) and human-independent realities (electrons, bioassays, objects, or planets,...) — so I'll just close this section with an example from science: Anyone who actually thinks that “beliefs create reality” should be eager to explain how the real motions of all planets in our solar system changed from earth-centered orbits in 1500 (when this was believed by almost everyone) to sun-centered orbits in 1700 (when this was believed by almost all scientists). Did the change in beliefs (from theories of 1500 to theories of 1700) cause a change in reality (with planets beginning to orbit the sun at some unspecified time between 1500 and 1700) ? No.

This final section — asking "Do scientists create reality?" — is adapted from Section 4C of a page asking "Should scientific method be eks-rated?"

|

APPENDIX #1 The two summaries below are from a page that asks Should scientific method be eks-rated? and "makes modest recommendations, based on a simple principle (that if a good idea is taken to extremes without sufficient balance from rational critical thinking, there may be undesirable consequences) and an assumption that undesirable consequences should be avoided."

The Limits of Logic (Summary for Section 2)Yes, there are limits. It is impossible, using any type of logic, to prove that any theory is either true or false. Why? If observations agree with a theory's predictions, this does not prove the theory is true, because another theory (maybe even one that has not yet been invented) might also predict the same observations, and might be a better explanation. But if there is disagreement between observations and theory-based predictions, doesn't this prove a theory is false? No, because the lack of agreement could be due to any of the many elements (only one of these is the theory being "tested") that are involved in making the observations and predictions, and in comparing them. Or the foundation of empirical science can be attacked by claiming that observations are "theory laden" and therefore involve circular logic, with theories being used to generate and interpret the observations that are used to support theories. This circularity makes the use of observation-based logic unreliable. And when this shaky observational foundation is extended by inductive generalization, the conclusions become even more uncertain. Yes, these skeptical challenges are logically valid. But a critical thinker should know, not just the limits of logic, but also the sophisticated methods that scientists have developed to cope with these limitations and minimize their practical effects. By using these methods, scientists can develop a rationally justified confidence in their conclusions, despite the impossibility of proof or disproof. We should challenge the rationality of an implication made by skeptics — that if we cannot claim certainty, we can claim nothing. Modern science has given up the quest for certainty, and has decided to aim for a high degree of plausibility, for a rational way to determine "what is a good way to bet."

Radical Relativism (Summary for Section 3)An extreme relativist claims that no idea is more worthy of acceptance than any other idea. Usually, relativism about science is defended by arguing that, when scientific theories are being evaluated, observation-based logic is less important than cultural factors. But if theories are determined mainly by culture, not logic, in a different culture our scientific theories would be different. And we have relativism. As with many ideas that seem extreme, radical relativism begins on solid ground. Most scholars agree with its two basic premises: the limits of logic and the influence of culture. But there is plenty of disagreement about balance, about the relative contributions of logic and culture in science, about how far a good idea can be extended before it becomes a bad idea that is harmful to rationality and society. This section ends by asking, “Does scientific knowledge improve over time?” Although a skeptic may appeal to the impossibility of proof and the fallibility of science, “the smart way to bet” seems obvious. To illustrate, imagine a million dollar wager involving a “truth competition” between scientific theories from the past, present, and future: from 1414, 2014, and 2114. Would a relativist really be willing to bet on theories from 600 years ago? |

|

APPENDIX #2 After deciding that the original version (below in unrevised form) was “TMI for most readers” it was replaced (in the main body of this page) by a condensed version. multiple definitions of ABSOLUTE TRUTHWhen a non-relativist makes claims about absolute truth, usually — unless the intended meaning is clarified — this will be confusing because "absolute truth" has many possible meanings: • If you intend a common meaning — a principle that is always true, in all cultures and situations, in the past, present and future — this universally-true principle should be called a universal principle or a general principle, not an absolute truth. If you explain what you mean by "absolute" this will clarify your intended meaning. • If you are making a truth-claim and are using a correspondence definition of truth, then absolute truth = truth, so adding "absolute" isn't necessary and it isn't helpful. Just call it a truth-claim and explain that when you say "truth" you mean correspondence-based truth, which is reality-determined truth. Doing this will clarify your intended meaning. / If you intend absolute truth to mean the opposite of relative truth, you are using the word "truth" in a way it should never be used, because this relative truth is not truth (and is not non-truth), instead it's a humanly constructed claim-about-truth (based on human criteria of consensus, or coherence, pragmatism,...) rather than any kind of truth. If another person refers to absolute truth or relative truth, maybe you can use this as a stimulus for a productive conversation about the biasing influence (which can be small or large) of the human context in which construction of the truth-claim is occurring. • If your truth-claim is about an independent reality, not a humanly constructed reality, explain the difference between these two types of reality. In this way, you can clarify your intended meaning. • If you have an extremely high level of confidence in a truth-claim, say “I'm absolutely certain that this is true” and explain why you are so confident. Saying this will clarify your intended meaning. / We should distinguish between absolute truth (which certainly does exist if we use a correspondence definition of truth) and absolute knowledge (which seems impossible for humans to achieve, although we can have an extremely high degree of logically-justifiable confidence). Because "absolute truth" is a term overpopulated with possible meanings, which can lead to confusion and misuderstanding. Therefore we should avoid this term (by replacing it with terms whose meaning is more precise) or (if a person really wants to use it) you should clearly explain the intended meaning. This is why I've emphasized the benefit of "clarifying your intended meaning" after describing each possible meaning. a strange use of terms: On rare occasions, someone compares absolute truth (but why use this term? what is the purpose? what is the intended meaning?) and relative truth (typically meaning some humanly-constructed belief) and replaces these terms by Truth (with a capital T) and truth (with a small t). But this subtle distinction (with & without capitalizing) typically isn't useful because many meanings are possible for Truth and truth, and often there is inadequate clarification of the intended meanings. This pair of terms also has an extra disadvantage, because truth (uncapitalized, so it means relative truth) uses "truth" in a way that should never be used. |