iou – February 26-28, I'll revise this section, that's in a "brown box" to show that it needs to be revised,

Experiments produce Experiences

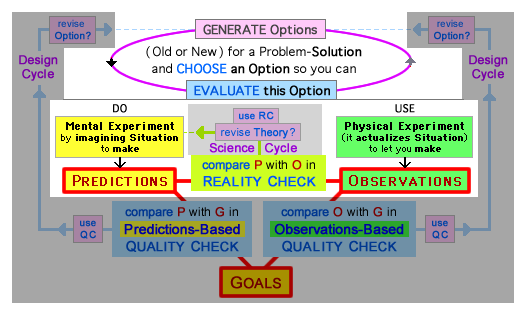

In the context of Design Process, an Experiment is any situation that produces Experiences and provides an opportunity to generate Experimental Information when you make Predictions (by imagining in a Mental Experiment ) or you make Observations (during the actualizing in a Physical Experiment ); i.e. any Prediction-Situation is a Mental Experiment, and any Observation-Situation is a Physical Experiment. Therefore instead of seeing "Experiment" (in Diagrams 2 & 3) and thinking “I don't do experiments,” you can recognize that most of your daily Experiences do involve Mental Experimenting (it's “what you think about”) and/or Physical Experimenting (it's "what you do").

Experimental Design: Designing Experiments is a useful skill, when you ask-and-decide "what will I think about?" (in Mental Experimenting to produce Mental Experiences) and "what will I do?" in Physical Experiments that produce Physical Experiences. A general strategy for inventing new Experimental Systems (E-Systems) is to creatively Generate Options for many possible E-Systems and “run them” in quick-and-easy Mental Experiments — to imagine “what kinds of things might happen, and what could we learn that might be interesting or useful” to make Predictions — and maybe Choose an E-System to actualize in a Physical Experiment. And you can remember (or find) old E-Systems, and choose to actualize one of them, as-is or modified. Or shift from this divergent search to a convergent search with focus, by asking “what do I want to know, and what Experiments will help me get this Information with useful Predictions or Observations?”

Predictions and Observations

how we make Predictions:

inductive reasoning: The most common way for a person to predict — it happens every time you “imagine what will happen” so Diagram 3 explains that “by imagining a Situation” you "make Predictions" — is by using logical experience-based induction. You do this by assuming that “what happened before (in similar situations) will happen again.” Asking “what is similar (in previous Situations & the current Situation) and what is different?” will help you do better Predicting, and have a level of confidence that is more appropriate.

deductive reasoning: But in some Situations a person uses logical theory-based deduction. How? Based on a Personal Theory (that often agrees with a Scientific Theory, but not always)* you use if-then logic by thinking “if My Theory (about how the world works, and what will happen) accurately corresponds to reality and what I expect to occur does occur, then will happen” and you fill the blank with your Prediction. {more about deductions}

deductive-plus-inductive: People usually combine these two kinds of logic (inductive & deductive) when we make Predictions, with the balance differing from one Prediction-Situation to another. This also happens in computer simulations — in forecasts for weather or climate; for football (in predictions about games, pre-game analysis of videos & data,...); with GPS (in suggestions for routes, predictions of ETA's); and in other simulations — that use a combination induction-and-deduction, with the balance differing from one kind of simulation to another.

things we predict : Obviously people predict “what will happen” or (more accurately) “what probably will happen” and you use these Predictions in Reality Checks. But in "what will happen" the "what" often predicts the characteristics of an Option that is being Evaluated (in a Quality Check) as a possible Problem-Solution. And when your objective is to design a Strategy – especially when it's a Strategy to improve a Relationship – you may predict the behaviors of people, of yourself or others, or both. Or during Experimental Design you can predict “what might happen” and “what could be learned” if you do an Experiment. And there are other possibilities, like those described in a research report about these four paragraphs that I will format – by writing a Table of Contents and making links (in that page and in this section) – during September 23-25.

how you make Observations:

When you DO a Mental Experiment "by imagining" you always "make Predictions." By contrast, a Physical Experiment just "lets you make Observations" because sometimes you USE the Experiment to make Observations, but you don't have to do this, so you don't always do it.

How and What? In some Experimental Situations you can make Observations directly with your internal human senses (to see, hear, touch, taste, smell) and/or indirectly with external measuring-instruments (a ruler, weighing scale, watch, thermometer,...). These two source-types let you get information that is qualitative or quantitative, can be represented verbally (with words,...) or visually (in graphs, photos or videos,...)

or mathematically (with numbers, equations,...) or in other ways.

simultaneously Observing-and-Predicting:

This occurs continuously in your everyday life because your Actions can be mainly (but not only) Mental, or mainly (but not only) Physical, or plenty of both with Physical-plus-Mental.

It will be easier to understand the what-how-why by thinking about examples from “ball sports” like basketball, football, and soccer. A basketball player who has the ball is making Observations (about where all players are now) AND is making Predictions (about where they will be soon) that are being compared with Goals (in Quality Checks) so they can make an Action-Decision about where to pass the ball, or to dribble it or shoot it. A skilled player can do the Problem-Solving Actions in Diagram 3 very quickly (in their system of subconscious-plus-conscious) so they can make a quick Action-Decision that is likely to be productive. At the same time, all other players (offensive & defensive) are Observing-Predicting-Comparing so they also can make productive Action-Decisions about where they will move and what they will do.

In your everyday Actions, you do similar “simultaneous Observing-and-Predicting” in a wide variety of different ways.

Defining Goals

Defining Goals is special kind of "Prediction" (actually it's "Predicting" because it isn't true Predicting but has many similarities along with a key difference), not Predn for probab of happening, but for imagining the desirability of future Goal-State state IF it happens. / true Predn --> WHAT might happen + PROBAB (HOW LIKELY)

into #eae

With a broad definition of Experiment most of your everyday Experiences involve Mental Experimenting and/or Physical Experimenting. The "and/or" includes "and" because people often do both kinds of Experimenting simultaneously. / pure Mental (common) but pure Physical (uncommon, usually is Physical-plus-Mental, P-and-M, @ws#dpmo-Intro for Actions, M P M-and-P)

using Old and New:

Diagram 3 says "GENERATE Options (Old or New) for a Solution" because you can Invent a New Option, or maybe – instead of “reinventing the wheel” – you will Find an Old Option and “use a wheel” (as-is or modified) if this will be an effective Problem-Solution. Both of these Actions, by Inventing or Finding, are ways to Generate an Option.

More generally, Old Knowledge (that already exists) can include Options (for a Solution or Theory) and also Problem-Situations & associated Solution-Goals; plus Experimental Systems (Mental or Physical) & associated Predictions or Observations.

You get Knowledge from Experiences, and your Total Experiences — in your First-Hand Experiences (happening to you) and Second-Hand Experiences (happening to others, but known by you) — include Knowledge that is Old (it's remembered in your personal memory or is found in our collective memory that is “culturally remembered” with books, web-pages, audio & video, etc; or it's learned directly from another person) so it's Old, but also is New (is being experienced now in your sensory perceptions & your thinking-and-feeling, is both conscious and subconscious). { finding-and-using Old Knowledge is Mode 2A in the 10 Modes of Action }

Your total experiences include your first-hand experiences with events you personally Observe (that you remember in your Personal Memory, from your own experience in the distant past or recent past) plus the second-hand experiences (found in our Collective Memory) that were Observed by someone else, then later (in a report or recording) you hear it and/or see it, or (in a web-page, tweet, book,...) you read about it.

combining Old and New: You want the best of both, for productive thinking that effectively combines relevant knowledge with creative thinking and critical thinking. You want a solid foundation of knowledge about what has been & now is (the Old & Present) plus flexible thinking that lets you freely imagine what could be (the New & Future). During your Process of Problem Solving when you're trying to Design a Satisfactory Solution, this combination lets you consider the full range of Old Options AND expand this range by creatively inventing New Options. / How? By using five Thinking Strategies Thinking Strategies for creatively using cognition-and-metacognition to Generate New Options. Thinking Strategies to Generate New Ideas.

two ways to learn:

iou – I'll revise this section during February 25-28, by revising the ideas below and supplementing them with ideas from other sections:

You can improve your understanding by learning from your discoveries – as in a Discovery Page — and also from my explanations.

Students are learning in both ways when you ask them to carefully study three diagrams — (Define and Solve), (3 Comparisons of 3 Elements), (Guided Generation in Design Cycles) — by examining each diagram and...

• asking “what is the meaning?” for every word & phrase, and (in the diagrams and their explanations-with-text) for the colors;

• asking “how are these two things connected?” for every arrow;

• thinking about “why the spatial relationships are logically meaningful” ...

and also (during each • ) thinking about how all of this describes the actions you use while you are solving problems. When you reflect on your own experiences, your Process of Discovery will become a Process of Recognition because you will recognize that Design Process accurately describes the Problem-Solving Actions that you use when you are solving problems. / also: Because problem solving has two wide scopes, people use a similar Problem-Solving Process for most Problem-Solving Activities, and these include almost everything we do in life.

applications for education: A classroom teacher can help students learn Principles for Problem Solving in both ways — from their discoveries (recognitions) and from explanations — during classroom activities that have been designed to guide students in a process of Experience + Reflection ➞ Principles that uses a process-of-inquiry to help them understand principles-for-inquiry, i.e. to understand principles for problem solving.

Because of this focus on their own actions, Discovery Learning (that actually is Recognition Learning) can work much better for learning procedural knowledge (i.e. Problem-Solving Process) than it does for learning declarative knowledge (aka factual knowledge); e.g. I know chemistry well, and almost everything I know is due to Learning from Explanations – by hearing and (especially) reading others – not Learning by Discovery.

[[ also -- link to ws#cmei or home#cmei -- and to #is0 early? ]]

EDU -- Your studying may stimulate you to think about the process of “doing Evaluations while you are Solving Problems” in new ways, or maybe it will show what you already have been thinking. / two ways to learn: I think you'll enjoy your discoveries, and also my explanations.

|

learning by discovering: When you explore the main diagrams in my model for problem solving, you will discover. You will understand the Problem-Solving Actions that people (you, me, and others) typically use when we are “making things better” by solving problems. These productive Actions are logically organized — so they're easier to understand, and are more effective for helping people (teachers & students, and others) improve their problem-solving skills — in my model for Design Process, i.e. for Problem-Solving Process.

learning by discovering: When you explore the main diagrams in my model for problem solving, you will discover. You will understand the Problem-Solving Actions that people (you, me, and others) typically use when we are “making things better” by solving problems. These productive Actions are logically organized — so they're easier to understand, and are more effective for helping people (teachers & students, and others) improve their problem-solving skills — in my model for Design Process, i.e. for Problem-Solving Process.

a basic roadmap: In a very simple model for problem solving, you choose an Objective (for what you want to improve) and understand “what is” in the NOW-State, and imagine “how it could be better” in a future GOAL-State. Then you do “problem solving” to convert The Now-State into a Desired Goal-State. / I found this Old Model – it's “public domain” (is not part of Design Process) – by

a basic roadmap: In a very simple model for problem solving, you choose an Objective (for what you want to improve) and understand “what is” in the NOW-State, and imagine “how it could be better” in a future GOAL-State. Then you do “problem solving” to convert The Now-State into a Desired Goal-State. / I found this Old Model – it's “public domain” (is not part of Design Process) – by  Design Process and SRL Cycles: This diagram-for-DP accurately shows the process used in a Cycle of SRL, with important details about the two stages of SRL when you mentally PLAN, then physically-and-mentally DO-and-Monitor. First, to "mentally PLAN" you "use [multiple] Mental Experiments to Generate-and-Evaluate Options [these are quick-and-easy compared with Physical Experiments, because you just “imagine what will happen” to make PREDICTIONS] and Choose an Option to USE." Second, to "physically DO and mentally MONITOR" you "USE this Option in [one] Physical Experiment [to physically DO] and [to mentally MONITOR, you] OBSERVE the Situation, your Actions, the Results." You complete the SRL Cycle by connecting the two stages (first PLAN, then DO-and-MONITOR), you "EVALUATE, asking ‘revise Option?’ in Design Cycle during re-PLAN." / the color-coding shows

Design Process and SRL Cycles: This diagram-for-DP accurately shows the process used in a Cycle of SRL, with important details about the two stages of SRL when you mentally PLAN, then physically-and-mentally DO-and-Monitor. First, to "mentally PLAN" you "use [multiple] Mental Experiments to Generate-and-Evaluate Options [these are quick-and-easy compared with Physical Experiments, because you just “imagine what will happen” to make PREDICTIONS] and Choose an Option to USE." Second, to "physically DO and mentally MONITOR" you "USE this Option in [one] Physical Experiment [to physically DO] and [to mentally MONITOR, you] OBSERVE the Situation, your Actions, the Results." You complete the SRL Cycle by connecting the two stages (first PLAN, then DO-and-MONITOR), you "EVALUATE, asking ‘revise Option?’ in Design Cycle during re-PLAN." / the color-coding shows